There are films whose disappointment hurts precisely because expectations were high. Gourou is one of them. With its topical subject, a respected director, and a leading actor known for his commitment, Yann Gozlan’s latest feature seemed poised to deliver a sharp, unsettling look at our era’s obsession with self-improvement and charismatic authority. Instead, it emerges as a frustrating work—one that circles an urgent theme without ever fully grasping it.

On paper, the premise is undeniably compelling. Gourou follows Matt Vasseur, a wildly successful personal development coach whose sold-out seminars and devoted followers suggest near-total influence. His ascent is suddenly threatened by the prospect of a Senate commission seeking to regulate a profession long operating in a grey zone, somewhere between empowerment and manipulation. In a cultural landscape saturated with motivational slogans, miracle promises, and aggressive “success coaching,” the film has fertile ground to explore collective vulnerability and the seduction of simple answers.

That exploration, however, remains largely theoretical.

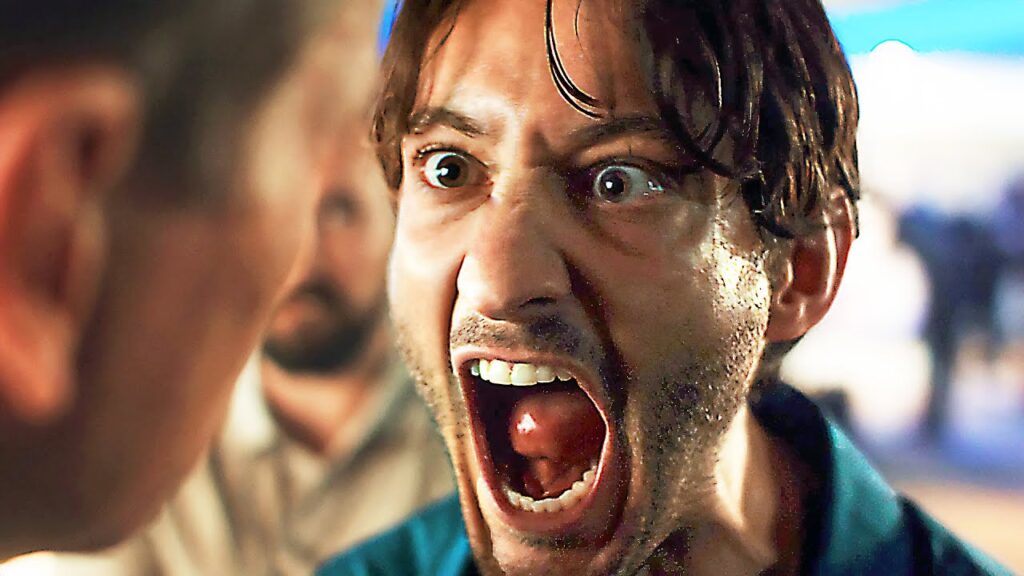

Pierre Niney, usually magnetic in morally ambiguous roles, is clearly invested in the character. His Matt Vasseur is unpleasant, self-absorbed, and occasionally chilling. Yet the essential element—the almost mystical power of persuasion that makes such figures dangerous—never quite materialises. We are told repeatedly that Vasseur electrifies crowds and reshapes lives with a few sentences, but we rarely feel it. The discourse is there; the grip is not.

The contrast becomes striking when the film introduces Vasseur’s American role model, played by Holt McCallany. In only a handful of scenes, McCallany exudes a natural authority and unsettling charisma that immediately commands attention. Against this presence, Niney’s character feels oddly muted, undermining the very foundation on which the story rests.

The screenplay is where Gourou truly loses its way. Determined to address everything at once—coaching culture, sect-like dynamics, media complicity, political power, family tensions, manipulation, and ultimately to morph into a thriller—the film spreads itself too thin. Narrative threads are introduced with promise, only to remain superficial or unresolved. Secondary characters hint at depth that never comes, and the film’s length only amplifies the sense of dispersion.

Subtlety, so crucial to this kind of subject matter, is sorely lacking. The film insists where it should suggest, explains where it should disturb. Despite genuine interest in the topic, moments of disengagement creep in—perhaps the most damning outcome for a story meant to provoke discomfort and reflection.

One particular choice crystallises this misjudgment: the appearance of French television personality Cyril Hanouna as himself. Rather than sharpening the critique of media spectacle, the cameo weighs it down, turning satire into caricature. It feels less like a thoughtful statement than a calculated nod to buzz culture, and it breaks the fragile balance the film struggles to maintain.

To be clear, Gourou is not a failure in technical terms. Yann Gozlan’s direction remains solid, the atmosphere is often effective, and flashes of unease suggest what the film might have been. There is an undeniable desire to say something meaningful about our time—about the cult of performance, the hunger for guidance, and the moral shortcuts taken in the name of success. After the razor-sharp control and narrative tension of Black Box, Gourou appears oddly scattered, as if unsure of its own priorities.

But by hesitating between thriller, social analysis, and satire, Gourou never fully commits to any of them. What lingers after the credits is not outrage or revelation, but frustration. And sometimes, that lingering disappointment is worse than indifference. As a cinematic start to 2026, it is a distinctly inauspicious one… thankfully we went ahead and saw Mercy with the excellent Chris Pratt at the night session right after Gourou to lift our hopes up.