In the history of literature, animals are never merely animals. They become mirrors, confidants, shadows of their masters’ souls. Among them, dogs occupy a singular place: loyal yet mysterious, grounded yet touched by myth. Certain writers—often in need of silent company—have found in their dogs not just affection but a source of rhythm, imagery, and even structure for their art. Here are five dogs who, in their quiet way, have left pawprints on the page of grand literature.

1. Pinka — Virginia Woolf’s Cocker Spaniel

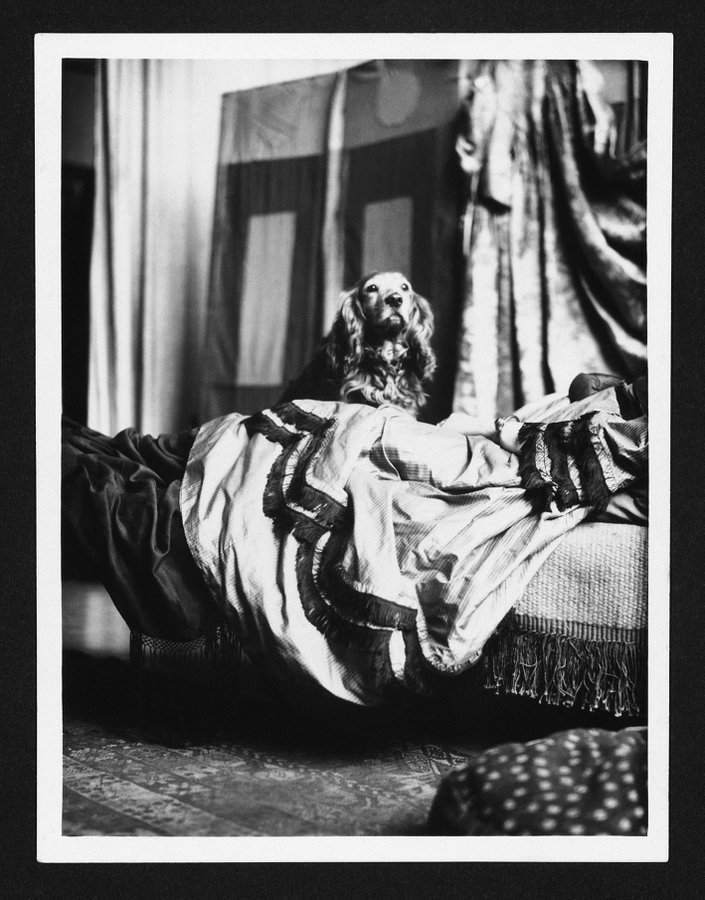

No dog is more entwined with the modernist imagination than Pinka, a black cocker spaniel given to Virginia Woolf by Vita Sackville-West. Pinka appears in letters, in diary entries, and even in photographs, often curled at Woolf’s feet or gazing into the distance with soulful eyes. She was more than a pet; she was an emissary between Woolf’s solitude and the world of touch and warmth.

Pinka presided over the writing of Flush (Woolf’s biography of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s spaniel), but she also became a kind of living metaphor for Woolf’s style itself: elegant, sensitive, attuned to nuance. Where human interlocutors exhausted her, Pinka offered quiet endurance. In the margins of despair, Woolf could reach out and touch fur, an anchor against the currents of her mind. Thus Pinka stands at the summit of literary dogs: a muse whose silence resonated through Woolf’s prose like an undertone of love.

2. Hachikō — The Dog of Haiku and Enduring Fidelity

Though not tied to a single poet, Hachikō, the Akita who waited every evening at Tokyo’s Shibuya Station for his deceased master, has inspired a body of literature that transcends borders. Japanese poets, novelists, and essayists have returned again and again to his story of patience and grief, transforming him into a parable of devotion.

Hachikō’s quiet vigil became a living haiku—seasonless, precise, charged with the poignancy of time. He is invoked in works of Yumi Hotta, Junichirō Tanizaki’s essays on loyalty, and countless modern haibun. His fidelity is less a quaint anecdote than a reminder of the metaphysical tether between beings. In Hachikō’s figure, literature found an image of loyalty that no human character could sustain without veering into myth. The dog waiting at twilight became the poem itself: unfinished, unending, unforgettable.

3. Carlo — Emily Dickinson’s Newfoundland

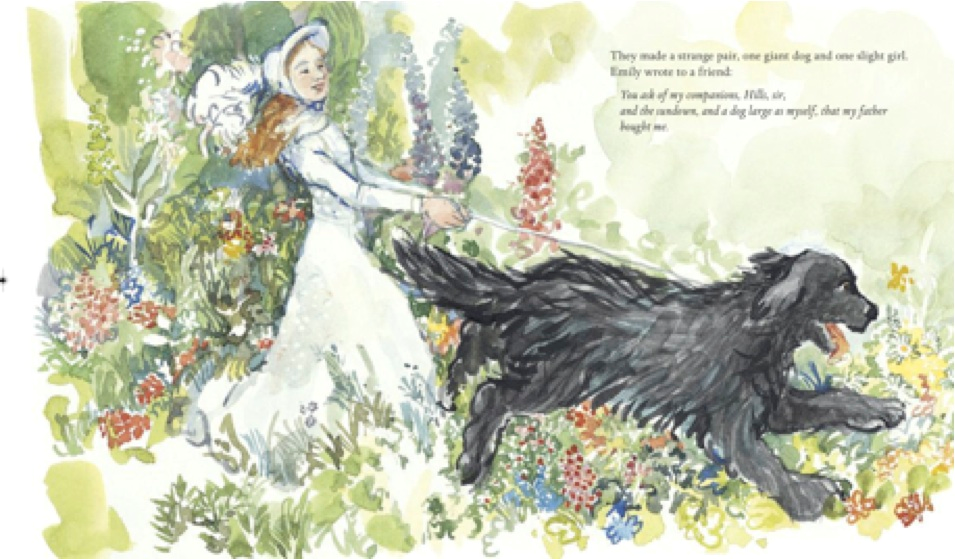

For the reclusive Dickinson, Carlo was no ordinary dog but an enormous presence in her intimate Amherst world. Given to her by her father when she was nineteen, Carlo accompanied Dickinson on long walks across the fields and hills. Where Dickinson chose solitude from human society, Carlo offered both protection and permission.

The dog appears in several letters as her “companion in liberty,” and when he died after sixteen years, Dickinson felt the loss as one feels the end of an epoch. Carlo’s absence resonates in the silence of her later poems. He was her wilderness and her witness, the one creature allowed to walk beside the most private poet in America. Without Carlo, Dickinson’s solitude might have tipped from fertile to barren. His great shadow runs quietly beneath her most intense lines.

4. Boatswain — Lord Byron’s Newfoundland

Byron, who lived by tempest and extravagance, poured some of his most heartfelt tenderness into a dog. Boatswain, his Newfoundland, died of rabies in 1808, and Byron erected for him one of the grandest monuments ever given to an animal. Inscribed upon it is Byron’s own “Epitaph to a Dog,” a poem at once bitter against humanity and exalted in praise of canine fidelity.

The monument still stands in Newstead Abbey, more imposing than Byron’s own memorial. In Boatswain, Byron saw not mere loyalty but the distilled virtue absent from humankind. The dog became a figure of purity against human corruption, and in exalting him, Byron wrote what may be literature’s most famous canine elegy.

5. Charley — John Steinbeck’s Poodle

If Byron monumentalized the dog in death, Steinbeck sought to rediscover America through the living presence of one. In Travels with Charley, Steinbeck sets out across the continent in 1960 with his standard poodle. Charley is no mere passenger; he is interlocutor, conscience, and fellow traveler.

Through Charley’s eyes—or rather, through Steinbeck’s tenderness toward Charley—the author reveals both the comic and the tragic in America’s vast landscape. Charley embodies companionship without judgment, a listener to whom Steinbeck can confess doubts about his country and his craft. He is a reminder that literature does not always emerge in cloisters or salons: sometimes it emerges on the open road, with a dog beside you and the horizon unfolding.

Dogs Have Always Been The Beating Heart of Writers’ Inspiration

To speak of dogs in literature is not to descend into anecdote but to recognize the profound, often wordless dialogue between human fragility and animal presence. From Woolf’s Pinka to Steinbeck’s Charley, these dogs shaped the cadence of their masters’ solitude, offering fidelity where words falter.

In their silence, they reminded writers of the deepest paradox: that literature, for all its brilliance, sometimes seeks only to imitate the gaze of a dog—steady, patient, unspoken, yet infinite in meaning.