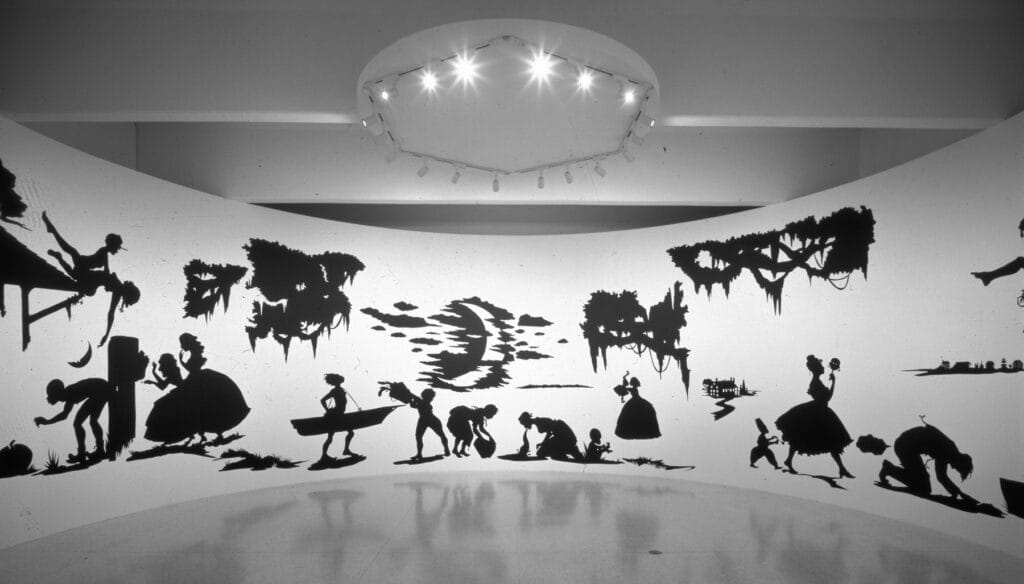

Kara Walker is one of the most significant and provocative artists in contemporary art today. Her works, often rendered in stark black silhouettes, delve into complex and painful themes, particularly the history of slavery in America, racial violence, gender, power dynamics, and their enduring legacies. Throughout her career, Walker has continuously challenged the traditional narratives of race and identity in the United States, forcing viewers to confront the uncomfortable truths of America’s past and their persistent effects on modern society. Her bold use of imagery and her willingness to tackle subjects that many would prefer to avoid have established her as a powerful voice in the art world.

Early Life and Background

Kara Elizabeth Walker was born on November 26, 1969, in Stockton, California, into a family immersed in creativity. Her father, Larry Walker, was an artist and professor of art, and his influence, alongside the diverse cultural environment of California, shaped her early exposure to art. However, when she was 13, her family moved to the South, settling in Stone Mountain, Georgia. This transition from the liberal atmosphere of California to the deep-seated racial tensions of the South played a formative role in her artistic trajectory. Stone Mountain, once the site of the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan, had a stark history of racial violence and segregation. The contrast between her Northern and Southern experiences introduced her to the uncomfortable reality of racial hierarchies and violence, themes that would permeate her later work.

Walker went on to receive a Bachelor of Fine Arts from the Atlanta College of Art in 1991, followed by a Master of Fine Arts from the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) in 1994. It was during her time at RISD that she developed her signature silhouette style, which would become her defining artistic language. The medium, traditionally associated with genteel 18th- and 19th-century portraiture, was transformed by Walker into a vehicle for disturbing and complex narratives about race and power.

The Evolution of the Silhouette and Narrative Power

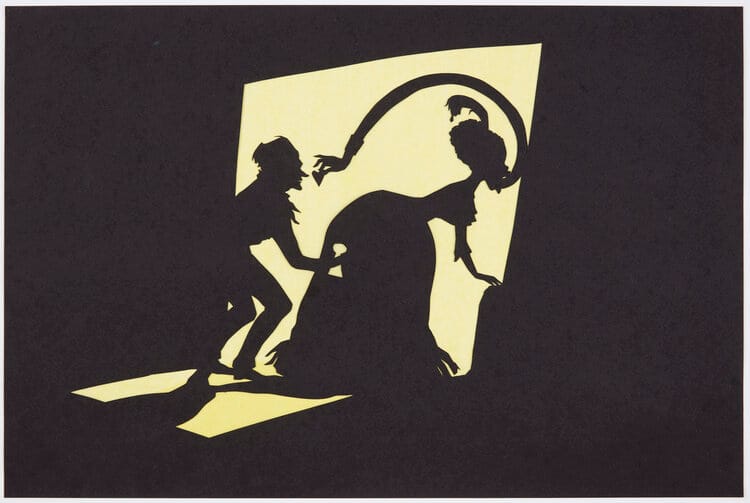

Kara Walker is most famously known for her large-scale, cut-paper silhouette installations, which she began producing in the mid-1990s. In these works, Walker appropriates the 18th- and 19th-century art form of the silhouette, which was often used to create delicate, genteel portraits of aristocrats and bourgeois families. By employing this medium in a new context, Walker subverts its original association with domestic refinement and politeness, turning it into a confrontational and violent examination of the legacy of slavery and racial oppression in America.

One of her breakthrough pieces, “Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War as it Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart” (1994), exemplifies the way in which Walker uses the silhouette to tell multi-layered stories. The title itself parodies the romanticized narratives of the antebellum South found in works like Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind, while the imagery depicted in the installation confronts the brutality of slavery head-on. Through a series of black cut-out figures mounted on white walls, Walker presents scenes of violence, exploitation, sexual coercion, and resistance, all set against the backdrop of Southern plantation life. This work immediately garnered attention for its fearless approach to depicting the complexities of history, race, and sexuality.

The power of the silhouette lies in its ambiguity. Devoid of facial expressions, the figures in Walker’s work allow viewers to project their own interpretations onto the scenes they witness. This abstraction forces the audience to grapple with their own biases, assumptions, and discomforts as they decode the disturbing scenarios Walker presents. The reductive nature of the silhouette also mirrors the reductive stereotypes that have been imposed on Black bodies throughout history, making the form itself an integral part of Walker’s commentary on race and identity.

Historical Memory and Trauma

Walker’s art draws heavily on the concept of historical memory, a theme that is central to understanding her importance in contemporary art. Her works often explore how societies remember, distort, or erase their own violent histories, particularly when it comes to slavery and racism in America. Walker’s art forces a confrontation with historical trauma—both personal and collective—by reimagining scenes from the past that still resonate today.

In “Slavery! Slavery! Presenting a GRAND and LIFELIKE Panoramic Journey into Picturesque Southern Slavery or ‘Life at ‘Ol’ Virginny’s Hole’ (sketches from Plantation Life)” (1997), Walker presents a nightmarish panorama of life on a Southern plantation. The work is filled with grotesque and exaggerated depictions of violence, rape, and racial degradation, challenging the audience’s understanding of the romanticized “Old South” often depicted in literature and film. By showing the horrors of slavery in such a graphic, even cartoonish, manner, Walker confronts the sanitized versions of history that obscure the brutal realities of America’s past.

This concept of challenging historical memory is also evident in “A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby” (2014), one of Walker’s most monumental and widely discussed installations. Commissioned by Creative Time and installed in the abandoned Domino Sugar Factory in Brooklyn, this massive work featured a 35-foot-tall sphinx-like sculpture of a Black woman made of sugar, surrounded by smaller molasses-covered boy figures. The work explicitly referenced the history of the sugar trade, which was deeply intertwined with the transatlantic slave trade, while also confronting the fetishization and commodification of Black bodies, both historically and in contemporary culture.

The choice of sugar as a material in this work was deeply symbolic, given sugar’s historical significance in the global economy and its role in the exploitation of enslaved Africans in the Caribbean and Americas. Walker’s installation served as both a tribute to the enslaved workers whose labor built empires and as a critique of how their suffering has been largely forgotten or minimized in the narratives of global capitalism. The work’s temporal nature—created from a material that would eventually degrade and melt away—mirrored the erasure of these histories from public memory.

Power, Gender, and Sexuality

In addition to addressing race and historical memory, Walker’s work frequently explores the intersections of power, gender, and sexuality. Her depictions of Black women often engage with the fraught history of their representation in art and society, as well as the ways in which their bodies have been subjected to violence, sexual exploitation, and objectification.

In her silhouettes, Walker frequently stages scenes of sexual violence, a reflection of the systemic rape of enslaved Black women by their white owners. These depictions are not simply intended to shock; rather, they are designed to draw attention to the ways in which power operates through the control and domination of bodies, particularly the bodies of Black women. By presenting these violent acts in silhouette form, Walker forces the viewer to confront the reality of sexual violence without being able to look away or downplay the severity of what is happening.

Walker’s work also critiques the myth of the “mammy” and the hypersexualized “Jezebel” stereotypes that have been used to dehumanize Black women throughout history. By appropriating and exaggerating these tropes in her art, Walker calls attention to their pervasive influence on contemporary understandings of Black femininity. In doing so, she challenges viewers to reconsider the ways in which they have internalized these harmful representations and to interrogate their role in perpetuating them.

Her exploration of gender and sexuality extends beyond the historical context of slavery. In works like “Testimony: Narrative of a Negress Burdened by Good Intentions” (2004), Walker delves into the complex dynamics of interracial relationships and the fetishization of Black women in contemporary society. This work, a combination of prints and video, tells the story of a Black woman and her white lover, exploring themes of domination, desire, guilt, and complicity. By intertwining personal narratives with historical references, Walker highlights the ways in which the legacies of slavery continue to shape contemporary relationships, both sexual and social.

The Reception of Kara Walker’s Work

Kara Walker’s work has been both celebrated and criticized for its unflinching portrayal of race, violence, and sexuality. Some viewers have praised her for bringing these difficult and often taboo subjects into the public sphere, using art as a tool for education and social critique. Others, however, have accused her of perpetuating harmful stereotypes or of exploiting Black trauma for the sake of shock value.

In particular, Walker’s use of grotesque and exaggerated imagery has led to debates about whether her work reinforces the very stereotypes it seeks to critique. Some critics have expressed concern that her art may be misinterpreted by viewers who lack the historical context necessary to understand its deeper meanings. Others have argued that her work can be retraumatizing for Black audiences, as it often depicts scenes of racial violence and degradation in graphic detail.

Walker herself has acknowledged these tensions, stating that her art is meant to provoke uncomfortable conversations and to challenge the viewer’s assumptions. In interviews, she has often spoken about the need to confront the dark aspects of history, rather than sweeping them under the rug or allowing them to be romanticized. Her work is not intended to provide easy answers or to offer a comforting resolution; instead, it is designed to unsettle, disturb, and provoke reflection.

Kara Walker’s Influence on Contemporary Art

Kara Walker’s influence on contemporary art is undeniable. She has expanded the boundaries of what art can address, introducing difficult conversations about race, gender, and power into the often insular world of fine art. Her work has inspired a new generation of artists to explore the intersections of identity, history, and social justice, using art as a platform for activism and social critique.

Walker’s work is often compared to that of other contemporary Black artists such as Kerry James Marshall, Glenn Ligon, and Theaster Gates, all of whom explore the complexities of Black identity and history in their art. However, her use of the silhouette and her explicit engagement with the legacy of slavery set her apart as a singular voice in contemporary art.

Walker’s art also resonates in broader cultural conversations about race and representation. In a time when discussions about systemic racism, police violence, and the legacy of slavery have become increasingly urgent, Walker’s work offers a critical lens through which to view these issues. Her art serves as a reminder that the past is never truly behind us; its legacies continue to shape the present in profound ways.

A Legacy of Provocation and Confrontation

Kara Walker’s importance in the realms of contemporary art lies in her ability to confront the darkest aspects of American history and to provoke difficult conversations about race, power, and violence. Through her stark, unsettling silhouettes and monumental installations, she has transformed the way we think about history, memory, and identity, forcing us to confront the painful legacies of slavery and racism that continue to haunt American society.

Her art serves as a powerful reminder that the past is never truly past—that the systems of oppression and exploitation that shaped America’s history still exert their influence today. By bringing these histories into the public eye and refusing to let them be forgotten or romanticized, Walker has cemented her place as one of the most important and provocative artists of our time. Her legacy is one of confrontation and provocation, challenging us to see the world—and ourselves—through a more critical and honest lens.