Tracey Emin has established herself as a pivotal figure in contemporary art, known for her radical confessional style that defies both societal taboos and conventional artistic forms. Emin’s works are grounded in autobiography, rendering private experiences as public discourses. Through an exploration of trauma, memory, femininity, and identity, Emin has redefined the boundaries of art, positioning it as a medium for intimate revelation and psychological confrontation. This approach, while groundbreaking, also positions her work within a lineage of artists who use self-disclosure as an aesthetic strategy, situating her within a broader historical and cultural discourse on the nature of authenticity and the body in art.

Theoretical Foundations and Artistic Influences

Emin’s oeuvre draws heavily on a framework rooted in both confessional art and feminist theory, foregrounding issues of selfhood, trauma, and gender as central to her practice. As a key member of the Young British Artists (YBA), Emin’s work emerged within a broader cultural movement characterized by a willingness to engage with sensationalism and a disregard for traditional “good taste.” However, while many YBAs focused on shock value and conceptualism, Emin’s art took a distinctively personal and affective approach.

Her influences range from the expressionist fervor of Edvard Munch and Egon Schiele to the psychologically charged sculptures of Louise Bourgeois. The resonance of these artists’ explorations of internal anguish, sexuality, and the body is evident in Emin’s work, which similarly seeks to materialize the intangible through art. Where Munch’s figures grapple with existential dread and Bourgeois’s sculptures confront the traumas of childhood, Emin’s practice transforms private moments into a visual language that speaks to the collective experience of pain, desire, and vulnerability.

The Confessional Mode: Autobiography as Aesthetic and Cultural Critique

Emin’s approach to art is inherently autobiographical, employing confessionalism as both an aesthetic and cultural critique. This methodology aligns her with the tradition of confessional poetry, as seen in the works of Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton, where personal revelation is transformed into an artistic method that blurs the boundaries between life and art. Emin’s confessionalism, however, is not merely an indulgence in personal narrative; rather, it serves as a platform to explore and critique social constructions of gender, sexuality, and mental health.

A prime example of this is her 1999 work My Bed, which consists of Emin’s unmade bed, surrounded by everyday items such as cigarette butts, empty liquor bottles, stained sheets, and crumpled tissues. Exhibited at the Tate Gallery and nominated for the Turner Prize, My Bed was controversial, igniting debates over whether such raw, autobiographical work could be considered art. By exposing her physical and emotional vulnerabilities, Emin challenged traditional notions of “acceptable” female behavior and aesthetics. My Bed not only invites viewers to gaze upon her intimate turmoil but also disrupts conventional representations of femininity, eschewing the sanitized, idealized depictions of women that pervade art history. Instead, she presents the reality of lived experience, underscoring the inseparability of personal trauma from the female body and identity.

Language as Liminal Space: The Power of Text in Tracey Emin’s Art

One of the most striking aspects of Emin’s work is her use of language, particularly in the form of text-based installations and neon sculptures. Her use of language is deeply interwoven with her visual art, transforming text into a medium that operates on the edge between the private and the public. This is exemplified in her 1995 work, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995, a tent embroidered with the names of individuals who have shared her bed, whether as lovers, friends, or family. Here, language becomes a vehicle for intimacy and connection, offering viewers an invitation into the nuanced fabric of Emin’s life.

In her neon installations, Emin repurposes language typically associated with commercial signs to articulate deeply personal sentiments. Phrases like “I Listen to the Ocean and All I Hear is You” or “You Forgot to Kiss My Soul” are inscribed in her own handwriting, emphasizing the authenticity of her voice. The medium of neon, often seen in public advertising, gives these statements an immediate, visual allure, yet the words themselves carry a profound intimacy that contrasts with their public display. This juxtaposition suggests a liminal space where private and public intersect, allowing viewers to engage with Emin’s internal dialogues and, by extension, their own.

The Female Body and the Politics of Representation

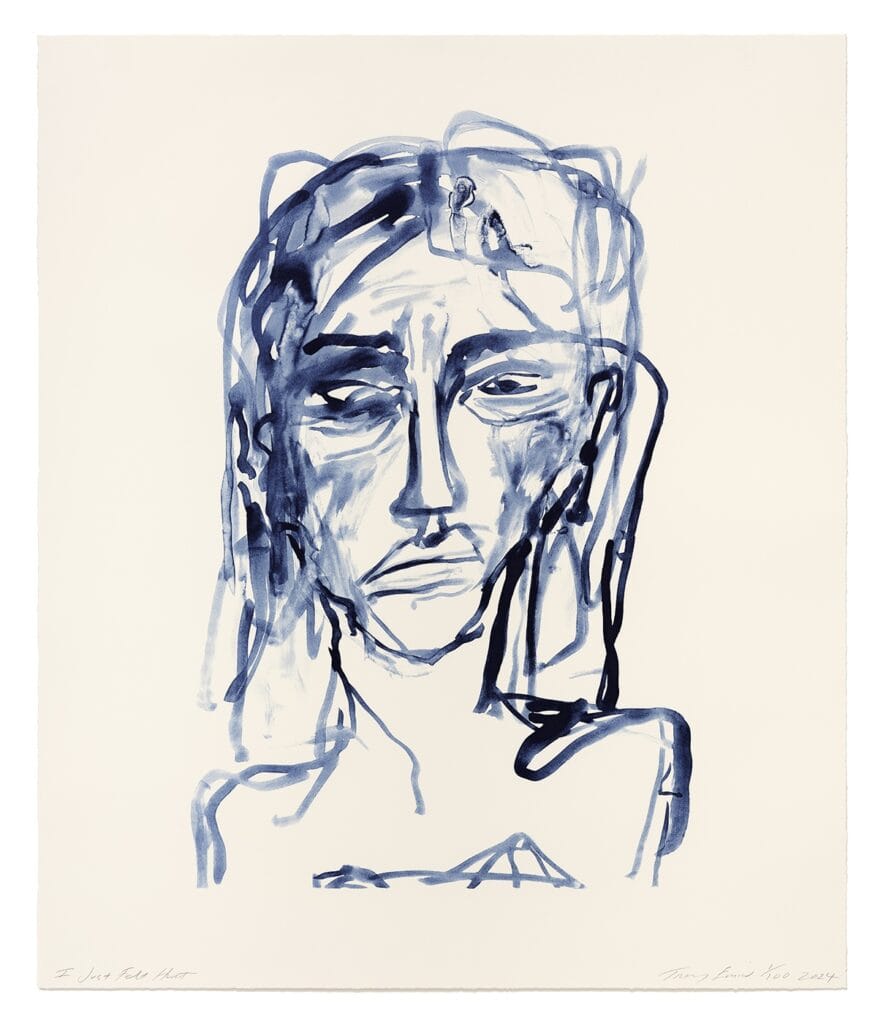

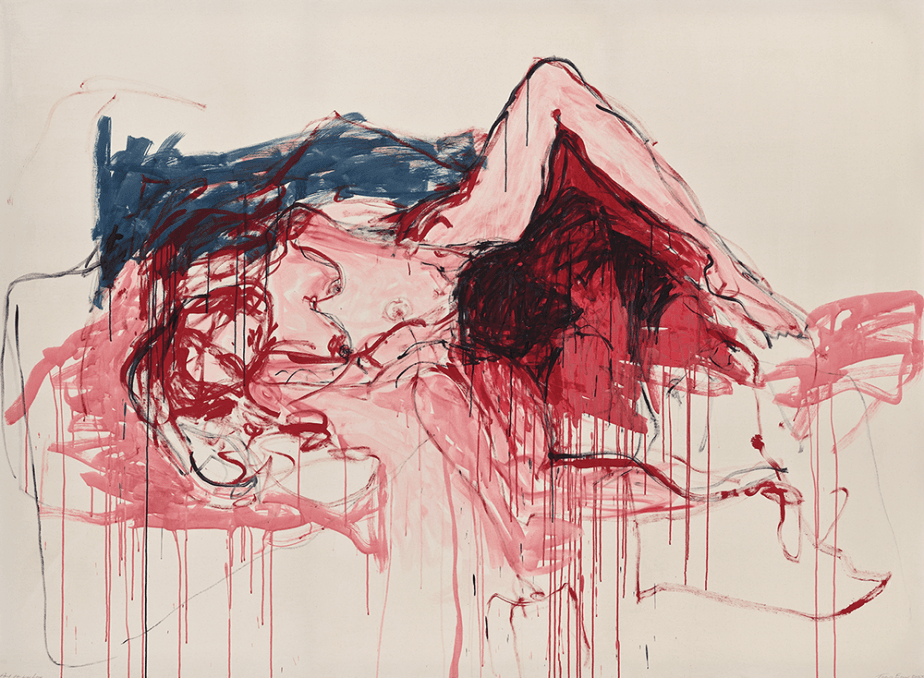

The representation of the female body is central to Emin’s work, which frequently features nude or semi-nude figures that reflect her unfiltered self-portrayal. Her works are often characterized by a lack of idealization; instead, they portray a body that is marked, scarred, and subject to the ravages of time and trauma. This approach disrupts the male gaze, positioning the female body not as an object of desire but as a site of suffering, resilience, and lived experience.

Emin’s exploration of the body often recalls the work of feminist artists like Carolee Schneemann and Ana Mendieta, who similarly used their own bodies as a medium to challenge and redefine gendered perspectives on sexuality and autonomy. Emin’s use of her own form underscores the subjective nature of bodily experience, emphasizing the ways in which bodies bear the physical and psychological imprints of personal history. Her paintings and monoprints often depict female figures that are abstracted and distorted, reflecting the fragmentation inherent in memory and trauma. These depictions reject the idealization of the female form that is so prevalent in art history, instead offering a raw and honest portrayal that confronts societal discomfort with female vulnerability.

The Role of Love, Loss, and Loneliness in Tracey Emin’s Art

Themes of love and loss are ever-present in Emin’s art, often explored through a lens of melancholy that imbues her work with a sense of universal pathos. Emin’s treatment of love and loneliness is deeply rooted in the Romantic tradition, which frames love as an all-consuming force that can lead to both transcendence and despair. Her works invite viewers to consider the complex relationship between love and identity, revealing how romantic attachment can both shape and distort the self.

The title of her 2014 neon sculpture, I Cried Because I Love You, encapsulates this tension, presenting love as a source of both joy and suffering. The piece exemplifies her ability to distill profound emotional experiences into simple yet evocative statements, allowing viewers to access the emotional weight of her work without needing to understand the specifics of her personal history. In doing so, Emin creates a bridge between the individual and the collective, using her own experiences as a conduit for exploring universal themes of human connection and isolation.

Time, Memory, and the Ephemeral

Memory is a recurring motif in Emin’s work, which often deals with the ephemeral nature of past experiences and the ways in which memories shape identity. Emin’s treatment of memory is fragmented, reflecting the selective, subjective nature of recollection. Her work does not aim to reconstruct the past in a linear or coherent manner; rather, it acknowledges the instability and fluidity of memory, suggesting that the past is not a fixed entity but an evolving part of the self.

This approach to memory aligns her work with postmodern theories of identity and temporality, which posit that the self is constructed through a series of fragmented and shifting narratives. Emin’s work engages with the notion of “autobiographical fiction,” a concept articulated by poststructuralist theorists such as Roland Barthes, who argued that autobiography is inherently subjective and that the “self” is a construct rather than a stable entity. Through her work, Emin explores the way memories are filtered through emotion and personal bias, thereby challenging the idea of memory as a reliable source of truth.

Tracey Emin’s Legacy and Influence on Contemporary Art

Tracey Emin’s work has had a profound impact on contemporary art, challenging traditional boundaries between life and art, public and private, and personal and universal. Her willingness to confront difficult topics and to expose her vulnerabilities has paved the way for a new generation of artists who use confessional and autobiographical approaches to explore issues of identity, trauma, and mental health. Emin’s work is a testament to the power of art as a medium for self-expression and social critique, revealing the ways in which personal experience can illuminate broader cultural and existential questions.

Emin’s legacy is characterized by her relentless pursuit of authenticity, her dedication to exploring the complexities of human emotion, and her refusal to conform to conventional expectations of femininity and beauty. By transforming her personal narrative into a public discourse, Emin has expanded the scope of what art can encompass, offering a space for viewers to confront and reflect upon their own experiences and vulnerabilities. Her work remains a powerful reminder of the capacity of art to evoke empathy, challenge societal norms, and give voice to the intricacies of the human condition.