Edward Ruscha, an artist whose name reverberates within the realms of Pop Art and Conceptual Art, stands as a paradoxical figure in contemporary art. His works encapsulate the quintessentially American ethos while simultaneously subverting it, revealing deeper layers of meaning beneath the glossy surface of everyday life. Ruscha’s oeuvre, characterized by its innovative use of text, evocative landscapes, and a distinctive Pop sensibility, defies easy categorization. This article delves into the multifaceted world of Edward Ruscha, exploring the intellectual underpinnings, creative innovations, and profound depth that define his art.

The Genesis of an Artistic Vision

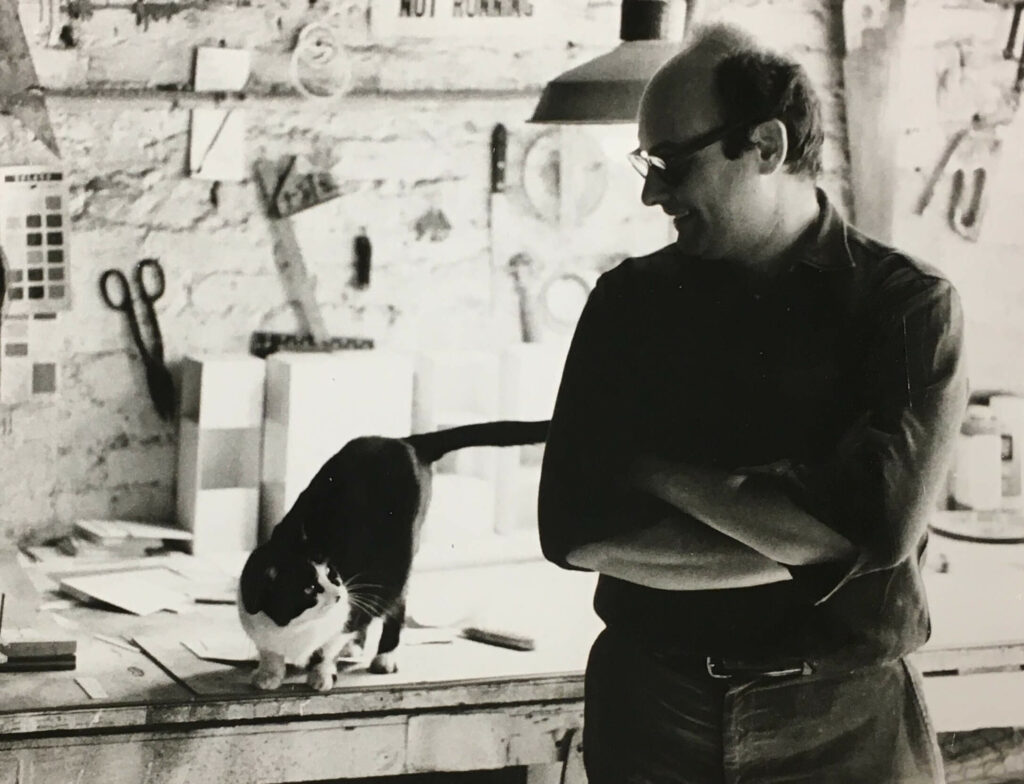

Edward Ruscha was born in 1937 in Omaha, Nebraska, and raised in Oklahoma City. His early fascination with art led him to move to Los Angeles in 1956 to study at the Chouinard Art Institute, now known as CalArts. The vibrant cultural milieu of Los Angeles, with its burgeoning art scene and the pervasive influence of Hollywood, played a crucial role in shaping Ruscha’s artistic vision. The city’s sprawling landscape, coupled with its unique blend of high and low culture, provided fertile ground for his burgeoning creativity.

Ruscha’s early works were deeply influenced by Abstract Expressionism, a movement that dominated the American art scene in the 1950s. However, he quickly diverged from its gestural and emotive style, seeking a more detached and cerebral approach. This shift was emblematic of a broader transition within the art world, as artists began to explore new forms and conceptual frameworks. Ruscha’s early experiments with painting and printmaking laid the foundation for his later work, which would come to define his distinctive artistic voice.

Words as Visual Objects: The Power of Text

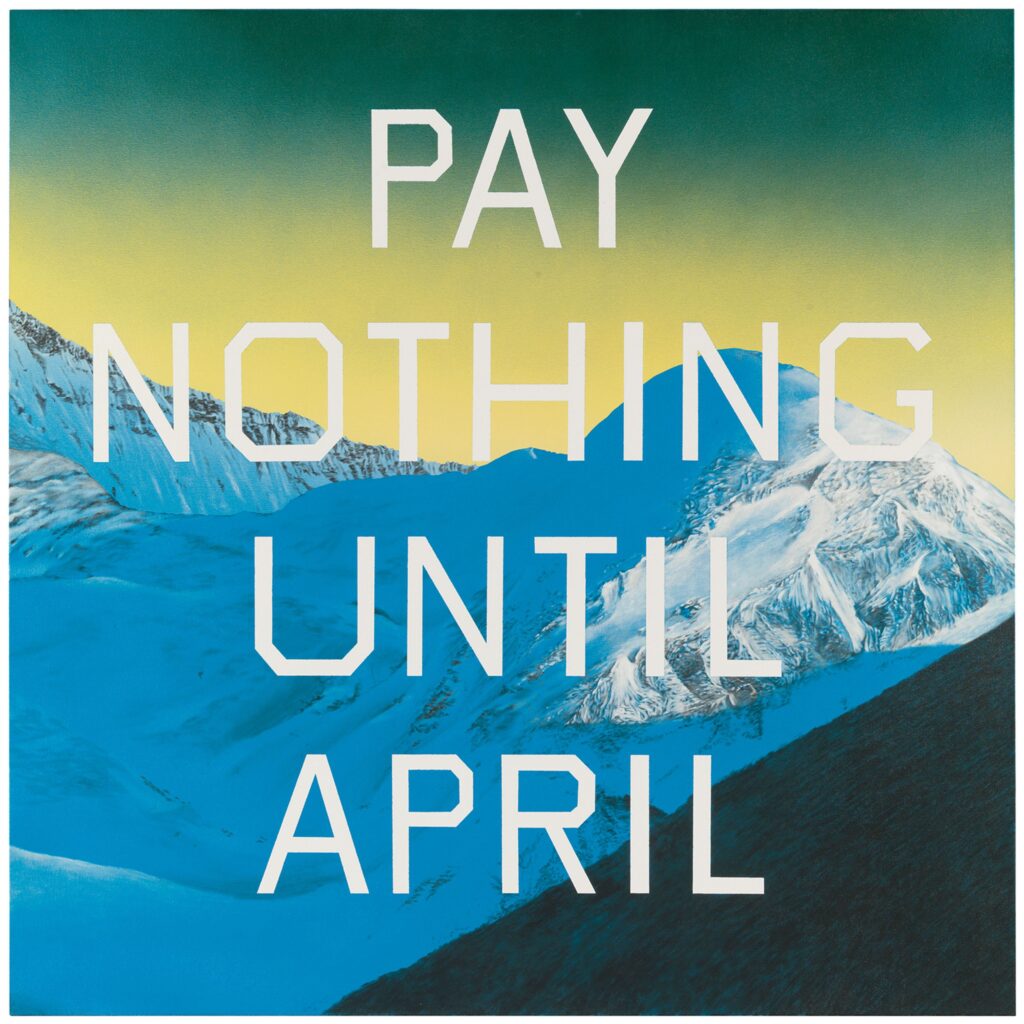

One of the most striking aspects of Ruscha’s work is his innovative use of text. Unlike many artists who employ language to convey explicit messages or narratives, Ruscha treats words as visual objects, imbuing them with a material presence that transcends their semantic meaning. This approach is evident in works such as “OOF” (1962) and “HONK” (1964), where single words are rendered in bold, graphic styles, floating against stark, monochromatic backgrounds.

Ruscha’s use of text is deeply influenced by the visual culture of Los Angeles, particularly the ubiquitous signage and billboards that punctuate the city’s landscape. By appropriating and decontextualizing these commercial graphics, Ruscha transforms mundane phrases into enigmatic symbols, inviting viewers to contemplate their intrinsic aesthetic qualities and underlying cultural connotations. This practice aligns him with the broader Pop Art movement, which sought to blur the boundaries between high art and popular culture.

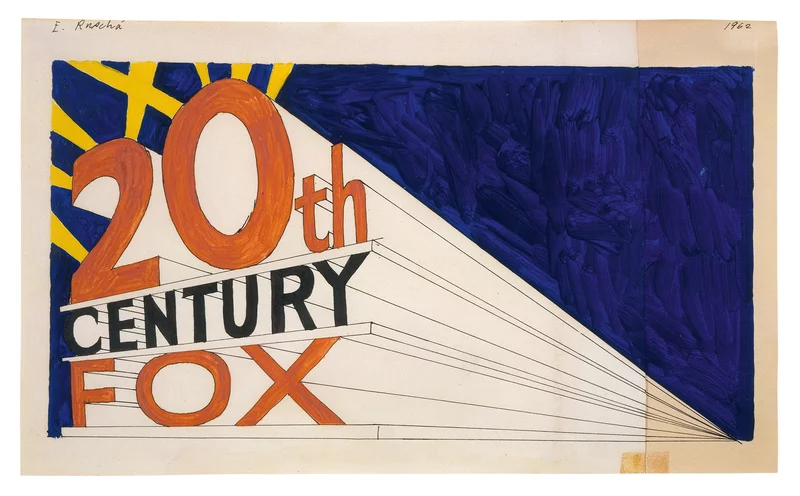

However, Ruscha’s engagement with text goes beyond mere appropriation. His works often evoke a sense of irony and ambivalence, reflecting the contradictions inherent in contemporary life. In “Large Trademark with Eight Spotlights” (1962), for instance, the familiar logo of 20th Century Fox is rendered with a meticulous attention to detail, yet its exaggerated scale and dramatic lighting lend it a surreal, almost absurd quality. This tension between familiarity and strangeness is a recurring motif in Ruscha’s work, challenging viewers to reconsider their perceptions of everyday imagery.

The Aesthetics of Landscape: Emptiness and Space

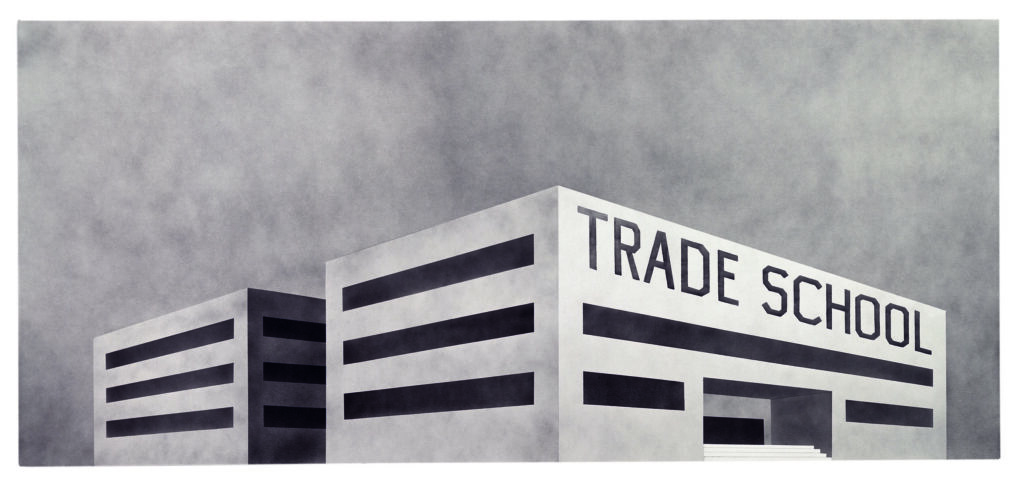

In addition to his text-based works, Ruscha is renowned for his evocative depictions of landscapes, particularly those of the American West. These works often feature vast, empty expanses punctuated by isolated structures or text, evoking a sense of desolation and introspection. This thematic preoccupation with space and emptiness can be traced back to Ruscha’s childhood in Oklahoma, where the flat, open plains left an indelible mark on his psyche.

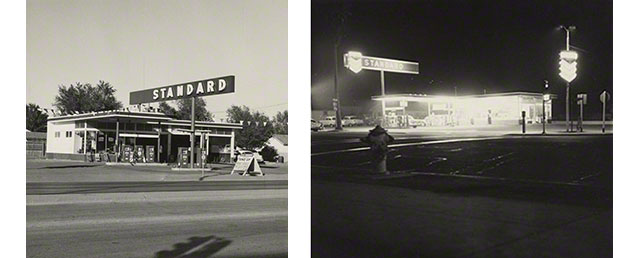

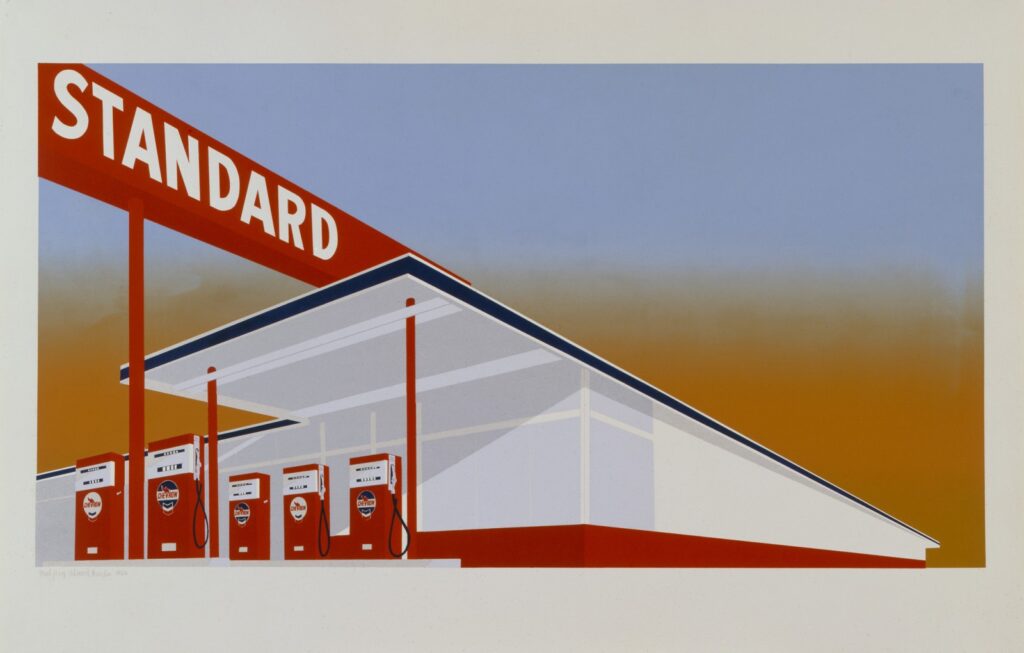

Ruscha’s landscapes are characterized by their meticulous attention to detail and atmospheric quality. In works such as “Standard Station” (1966) and “Twentysix Gasoline Stations” (1963), he captures the stark, utilitarian architecture of gas stations against expansive, featureless backdrops. These images, devoid of human presence, evoke a sense of loneliness and isolation, underscoring the transient nature of modern life. The gas stations, with their clean lines and minimalist design, also serve as symbols of American consumer culture, embodying both its promise of mobility and its underlying emptiness.

Ruscha’s landscapes are not merely representations of physical spaces; they are also psychological landscapes, reflecting the artist’s internal world and broader cultural anxieties. The empty highways and deserted buildings become metaphors for the existential void at the heart of contemporary existence, inviting viewers to contemplate their own place within this vast, indifferent universe. This existential dimension of Ruscha’s work aligns him with the broader tradition of American landscape painting, from the sublime vistas of the Hudson River School to the stark, introspective works of Edward Hopper.

Conceptual Innovation: Books and Seriality

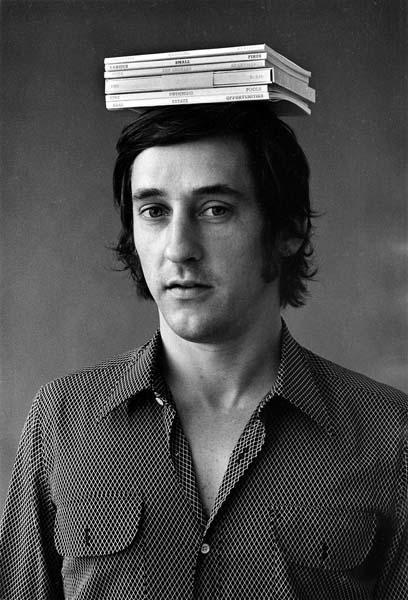

A key aspect of Ruscha’s practice is his innovative use of books as artistic mediums. Beginning with “Twentysix Gasoline Stations” (1963), Ruscha produced a series of self-published artist books that documented mundane aspects of American life in a detached, serial manner. These books, which include titles such as “Every Building on the Sunset Strip” (1966) and “Nine Swimming Pools and a Broken Glass” (1968), are characterized by their minimalist design and deadpan aesthetic.

Ruscha’s books are significant not only for their content but also for their form. By presenting photographs in a straightforward, unadorned manner, Ruscha subverts traditional notions of artistic authorship and narrative. The repetitive, grid-like structure of these books emphasizes the banality of their subject matter, while also inviting viewers to consider the underlying patterns and rhythms of everyday life. This serial approach reflects Ruscha’s broader interest in systems and structures, aligning him with the Conceptual Art movement.

Moreover, Ruscha’s books challenge conventional definitions of art by blurring the boundaries between different media. By incorporating elements of photography, design, and literature, these works create a hybrid form that defies easy categorization. This interdisciplinary approach is emblematic of Ruscha’s broader practice, which consistently pushes the boundaries of artistic expression and invites viewers to question their assumptions about art and culture.

The Interplay of Humor and Melancholy

A distinctive feature of Ruscha’s work is its unique blend of humor and melancholy. His art often employs irony and wit to comment on the absurdities of modern life, yet beneath this playful exterior lies a deeper sense of introspection and existential angst. This duality is evident in works such as “Annie, Poured from Maple Syrup” (1966), where the cheerful, cartoonish image of Little Orphan Annie is rendered in a viscous, amber substance, creating a disconcerting contrast between form and content.

Ruscha’s use of humor serves multiple functions. On one level, it provides a means of engaging viewers, drawing them into his work with its accessible, relatable imagery. However, this initial sense of familiarity is often subverted by a deeper, more unsettling layer of meaning. In “Hollywood” (1968), for example, the iconic sign is depicted as a distant, fading presence, shrouded in mist. This image, while ostensibly a celebration of Hollywood’s glamour, also hints at its ephemeral, illusory nature, revealing the emptiness beneath the surface.

This interplay of humor and melancholy is a recurring motif in Ruscha’s work, reflecting his ambivalent relationship with contemporary culture. His art captures the contradictions and complexities of modern life, juxtaposing the banal and the sublime, the humorous and the tragic. This nuanced approach challenges viewers to engage with his work on multiple levels, encouraging them to look beyond the surface and explore the deeper currents of meaning that run beneath.

The Everlasting Anti-Mundanity of Edward Ruscha

Edward Ruscha’s impact on contemporary art is profound and far-reaching. His innovative use of text, landscape, and seriality has influenced a diverse range of artists, from Pop Art pioneers like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein to contemporary practitioners such as Barbara Kruger and Richard Prince. Ruscha’s ability to merge high and low culture, to transform the mundane into the sublime, has left an indelible mark on the art world.

Moreover, Ruscha’s interdisciplinary approach has paved the way for new forms of artistic expression, challenging traditional boundaries and encouraging a more fluid, inclusive understanding of art. His work, with its blend of conceptual rigor and aesthetic appeal, continues to resonate with audiences, offering fresh perspectives on the complexities of contemporary life.

In conclusion, Edward Ruscha’s art is a rich tapestry of visual and conceptual innovation, characterized by its engagement with language, landscape, and popular culture. His work invites viewers to explore the deeper layers of meaning beneath the surface of everyday imagery, revealing the contradictions and complexities of modern life. Through his unique blend of humor and melancholy, Ruscha captures the essence of the contemporary experience, offering a poignant commentary on the transient, multifaceted nature of existence. As we continue to navigate the ever-changing landscape of the 21st century, Ruscha’s art remains a vital touchstone, reminding us of the power of creativity to illuminate the hidden dimensions of our world.