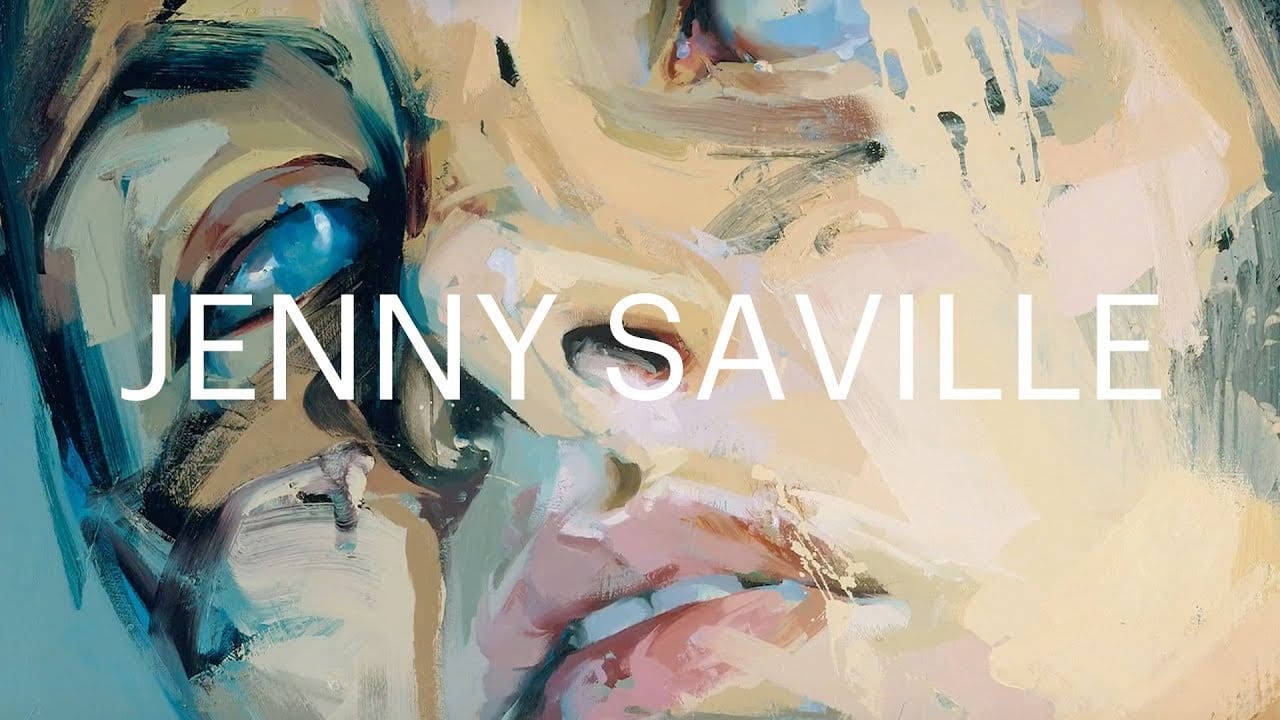

Jenny Saville’s art emerges as a powerful confrontation with the human form, where the body—often female, often voluminous, sometimes fragmented—is portrayed not as an object of passive observation but as an arena for active, visceral experience. Born in 1970, Saville has risen to become one of the most compelling and influential contemporary British painters, renowned for her confrontational depictions of flesh and her exploration of the body in all its myriad forms—its beauty, its violence, its vulnerability, and its raw, unadorned truth.

Her works reflect a deep engagement with issues of gender, identity, and the human condition. By drawing inspiration from classical traditions, medical imagery, feminist theory, and photography, Saville has crafted a body of work that invites viewers to reconsider how they perceive the physical self. Her paintings resonate with a blend of tenderness and brutality, seeking to challenge societal norms while pushing the boundaries of what the human body in art can express.

Flesh as Medium: Exploring the Materiality of the Body

At the heart of Jenny Saville’s work is an unwavering preoccupation with flesh—the visceral, corporeal aspect of existence that is both familiar and alien to us. Her paintings are monumental in scale, often spanning several meters, demanding that the viewer confront them with the same immediacy that one might experience in front of an actual body. However, what sets Saville’s portrayal of flesh apart is the palpable tension between the material and the metaphysical.

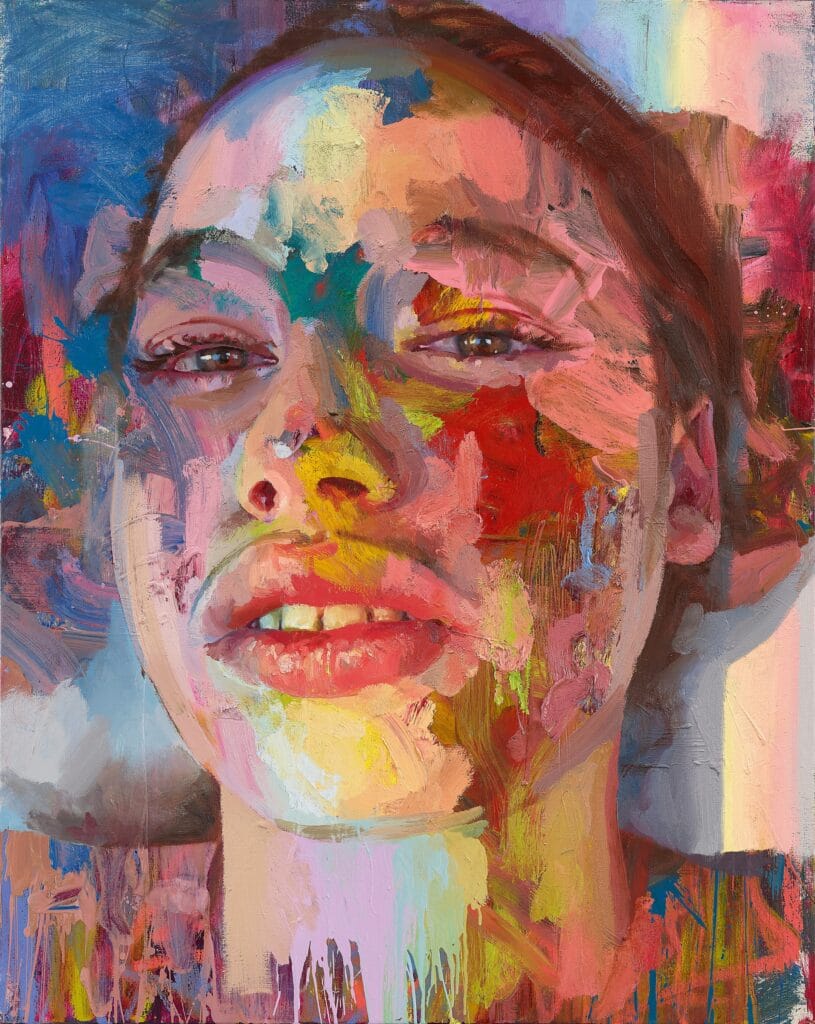

Flesh in Saville’s paintings is not merely skin or surface; it is a dynamic, mutable substance that seems to pulse and breathe. The texture of skin in her works oscillates between sensuality and grotesqueness, oscillating between tender softness and bruised decay. Her brushstrokes, bold and sweeping, emphasize the weight and volume of the body, portraying it as a mass in constant flux. One can see echoes of the classical masters, from Rubens’ opulent women to Titian’s fleshy nudes, yet Saville’s approach is distinctly contemporary, as she deconstructs and reconfigures the body into something altogether different—a site of tension, conflict, and inquiry.

Her early series of works, such as Propped (1992) and Plan (1993), exemplify this exploration of the materiality of flesh. In Propped, the viewer is met with a large, nude female figure perched awkwardly on a stool, her body disproportionately massive. Her skin is rendered in thick, textured layers of paint that evoke both the delicacy and the burden of inhabiting such a form. The body is twisted, compressed, and angled in a way that evokes discomfort, both physically and emotionally, as the viewer is forced to grapple with its weight and presence. Here, Saville is not merely interested in representing the female body; she seeks to communicate the experience of being in that body—the sensation of living within flesh, with all its attendant pain and pleasure.

In Plan, Saville’s engagement with medical imagery becomes even more explicit. The painting depicts a nude woman, her body inscribed with lines that suggest a surgical plan for liposuction, as though she were a map to be altered and improved. Yet the woman’s expression—stoic, almost defiant—suggests a resistance to the implied violence of this transformation. The body here becomes a battleground, where societal expectations of beauty and perfection are challenged by the reality of the flesh. Saville’s use of mapping and marking directly references the way in which women’s bodies are subjected to control and modification, not only through surgery but through cultural standards of femininity and beauty.

Deconstructing Gender: The Politics of the Female Body

Saville’s art is deeply feminist, though she resists easy categorization. Her portrayals of the female body do not conform to traditional standards of beauty, nor do they fit neatly within the realm of protest art. Rather, Saville’s work occupies a space of profound ambiguity, where the boundaries between power and vulnerability, autonomy and objectification, are constantly shifting.

One of her most iconic works, Rubens Flap (1999), is a striking example of how she deconstructs and reimagines the female body. The painting shows a fleshy torso, seemingly genderless at first glance, its skin sagging and folding in unnatural ways. It is a body in the process of transformation, not entirely human, yet not completely abstract. The viewer is left to question the nature of this figure—is it a victim of violence or surgery? Is it a body in decay, or a body in metamorphosis? Saville offers no clear answers, instead presenting the body as a site of ambiguity and complexity.

Saville’s engagement with gender also extends beyond the female form. In works such as Passage (2004) and The Mothers (2011), Saville explores themes of motherhood, pregnancy, and the transformation of the female body through childbirth. These works confront the viewer with the physical and emotional weight of motherhood, depicting bodies swollen and stretched, yet imbued with a sense of power and strength. The figures in these paintings are not idealized mothers, nor are they victims of their biological fate. Instead, they are monumental, almost godlike in their presence, embodying both the pain and the beauty of creation.

The Fragmented Self: Identity, Body, and Transformation

Saville’s exploration of the body often leads her to question the nature of identity itself. In her later works, such as The Matrix (2013-14) and Shadow Head (2018), Saville shifts away from the singular, monumental body and toward the fragmented, the multiple, and the disjointed. These works feature layered, overlapping images of faces and bodies, as though the figures are caught in the process of becoming, their identities in flux.

The Matrix, for example, presents a chaotic swirl of faces, limbs, and torsos, layered one on top of the other in a seemingly endless cycle of transformation. The effect is both disorienting and mesmerizing, as the viewer is drawn into the complexity of the image, unable to settle on any one figure or identity. Here, Saville seems to be questioning the very notion of a stable, unified self, suggesting that identity is always in a state of flux, constantly shifting and evolving.

This theme is further explored in Shadow Head, a haunting portrait of a face that seems to dissolve into darkness. The face is both present and absent, its features obscured by shadow and smudged layers of paint. It is as though the figure is caught in the process of disappearing, its identity slipping away. This sense of fragmentation and dissolution speaks to a broader concern in Saville’s work: the idea that the body, and by extension the self, is always in the process of becoming, never fixed or complete.

Engaging with Art History: A Dialogue with the Past

Saville’s work is deeply rooted in art history, yet she engages with the past in a way that is both reverent and subversive. Her monumental nudes recall the grandeur of classical painting, particularly the works of the Old Masters such as Rubens, Titian, and Michelangelo. However, where the Old Masters often idealized the female form, presenting it as an object of beauty and desire, Saville’s figures are raw, unpolished, and unapologetically real.

In works such as Torso II (2004), Saville directly references the tradition of the classical nude, yet her portrayal of the body is far from idealized. The figure’s flesh is mottled and bruised, its form awkward and contorted. There is a sense of violence in the way the body is depicted, as though it has been subjected to both physical and emotional trauma. Yet at the same time, there is a tenderness in the way Saville handles the paint, a sense of care and empathy for the subject. This tension between brutality and compassion is a hallmark of Saville’s work, and it is through this tension that she creates a new, more complex understanding of the human body in art.

Saville’s engagement with art history also extends to her use of materials and techniques. Her paintings often feature thick, textured layers of oil paint, applied with broad, sweeping brushstrokes that recall the work of painters such as Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon. However, where Freud’s and Bacon’s figures often seem trapped within their own flesh, Saville’s figures are in constant motion, their bodies shifting and transforming before our eyes. This dynamic quality is heightened by Saville’s use of photography and digital manipulation, which she often incorporates into her process, creating a sense of fluidity and movement within her paintings.

The Power of Paint: Saville’s Artistic Process

Jenny Saville’s process is as much a part of her art as the finished paintings themselves. She is known for her meticulous attention to detail, spending months or even years on a single work, layering paint upon paint until the surface of the canvas becomes almost sculptural in its texture. Her use of color is equally deliberate, with each hue carefully chosen to evoke the physicality and emotion of the flesh.

Saville often begins her process by working from photographs, both of herself and of models, which she then manipulates and distorts to create the compositions for her paintings. This use of photography allows Saville to explore the body in ways that go beyond traditional painting, as she is able to experiment with scale, perspective, and distortion in ways that would be impossible with a live model.

Once she has settled on a composition, Saville begins the process of painting, applying layers of oil paint with bold, expressive brushstrokes. Her approach to paint is almost sculptural, as she builds up the surface of the canvas, creating a sense of weight and volume in her figures. The result is a body of work that is both tactile and visual, inviting the viewer to engage with the materiality of the paint as much as with the image itself.

The Artistic Theory of Jenny Saville

Jenny Saville’s work stands as a profound exploration of the human body, both in its physical form and as a site of cultural, social, and personal meaning. Her paintings challenge the viewer to confront the complexities of flesh, identity, and transformation, offering a new way of seeing and understanding the body in art. Through her engagement with art history, feminist theory, and contemporary culture, Saville has created a body of work that is both deeply personal and universally resonant.

In a world where the female body is often commodified and objectified, Saville’s work offers a powerful counter-narrative. Her figures are not passive objects of the gaze; they are active, autonomous beings, imbued with a sense of agency and presence. They are bodies that resist easy categorization, bodies that exist in a state of constant flux and transformation. In this way, Saville’s work speaks to the broader human condition, reminding us that the body, like the self, is always in the process of becoming.

Ultimately, Jenny Saville’s art invites us to look beyond the surface, to see the body not as a fixed entity but as a dynamic, ever-changing force. Her paintings challenge us to reconsider our own relationship to our bodies, to question the societal norms that shape our perceptions of beauty and identity, and to embrace the complexity and ambiguity of the human form. Through her visceral, powerful depictions of flesh, Saville has created a new language of the body, one that is as raw and real as it is beautiful. In doing so, she has cemented her place as one of the most important and influential artists of our time.