In the annals of late 20th-century cinema, Buffalo ’66 exists not merely as a film, but as a raw nerve, an open wound, a cinematic poem scrawled in the margins of a society preoccupied with superficiality. Directed, written, and embodied by the mercurial Vincent Gallo, this 1998 indie magnum opus defies categorization, transcending the boundaries of conventional filmmaking to become an elegy for the disenchanted and the dispossessed. Through its harrowing narrative, fragmented aesthetic, and searing psychological insight, Buffalo ’66 offers a bleak yet beautiful meditation on the existential void that lies at the heart of modern existence.

A Parable of the Damned: The Existential Landscape of Buffalo ’66

At its core, Buffalo ’66 is a study in dislocation—a narrative of a man who exists on the periphery of life, exiled not by external forces, but by the internal cacophony of his own fractured psyche. Billy Brown (Vincent Gallo), a man-child lost in the barren expanses of Buffalo, New York, is not merely a character but a cipher—a representation of the postmodern anti-hero, caught in the throes of ennui and self-loathing. His return to his hometown, after a five-year imprisonment for a crime he did not commit, is less a homecoming and more a pilgrimage to the ruins of his former self.

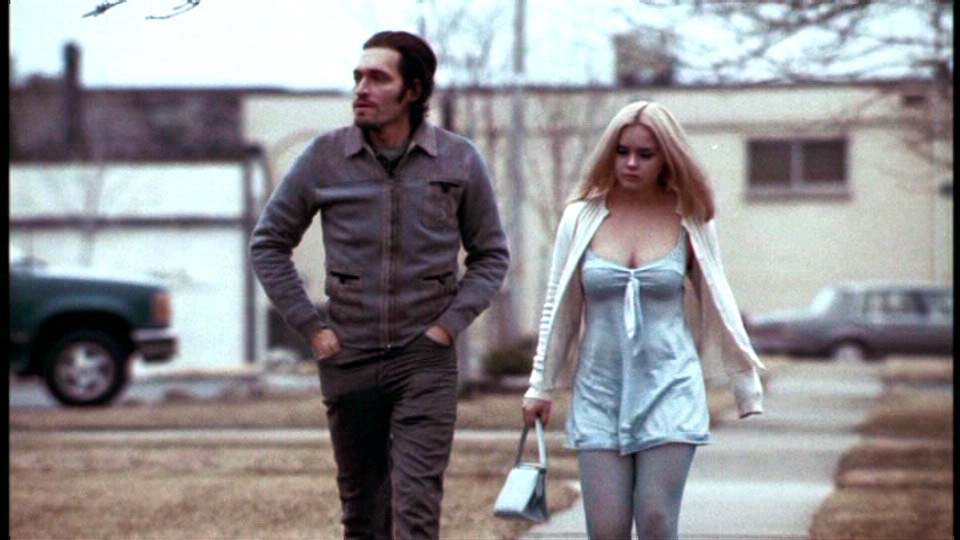

Gallo’s performance as Billy is an exercise in controlled volatility. His every gesture, every glance, is fraught with the tension of a man who teeters on the edge of emotional implosion. Billy’s kidnapping of the ethereal Layla (Christina Ricci), a tap-dancing waif whom he coerces into posing as his wife, is a desperate attempt to construct a façade of normalcy in a life defined by chaos. Yet, beneath this surface narrative lies a deeper subtext—a commentary on the futility of the human quest for meaning in a world that is inherently meaningless.

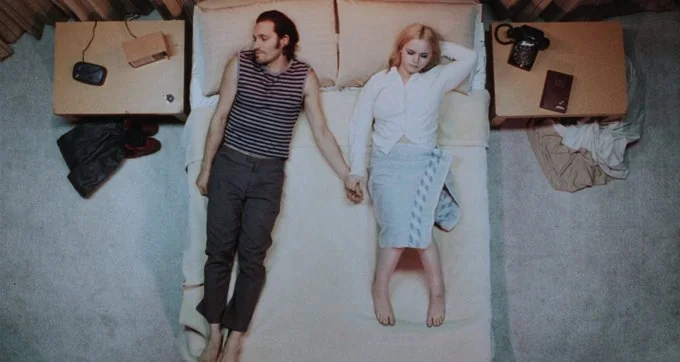

The film’s existential undercurrent is further underscored by its narrative structure, which eschews linearity in favor of a fractured, dream-like progression. Time in Buffalo ’66 is not a steady river, but a turbulent sea—its currents unpredictable, its depths unfathomable. The film’s fragmented chronology, punctuated by flashbacks and surreal interludes, reflects Billy’s disoriented mental state, creating a narrative that is as disjointed and disorienting as the protagonist’s fractured reality.

Aesthetic Nihilism: The Stark Visual Poetry of Buffalo ’66

Visually, Buffalo ’66 is a masterclass in aesthetic minimalism, its stark cinematography serving as both a mirror and a magnifier of the desolate world it depicts. The film’s color palette—dominated by cold, washed-out hues of gray, blue, and brown—evokes the bleakness of the industrial wasteland that is Buffalo, a city frozen in a perpetual winter of decay. This visual desolation is contrasted by the film’s sporadic bursts of color, most notably in the figure of Layla, whose vibrant presence offers a fleeting glimpse of warmth and hope in an otherwise monochromatic world.

Gallo’s use of unconventional framing and editing techniques further heightens the film’s aesthetic dissonance. The claustrophobic close-ups, the off-kilter angles, and the abrupt cuts all serve to disorient the viewer, mirroring Billy’s own sense of dislocation and alienation. These stylistic choices are not mere affectations, but deliberate attempts to disrupt the viewer’s sense of visual comfort, forcing them to engage with the film on a deeper, more visceral level.

The soundtrack, curated with obsessive precision by Gallo, is a sonic tapestry that weaves together disparate threads of 1970s rock, classical music, and original compositions. The juxtaposition of Yes’s “Heart of the Sunrise” with moments of intense emotional turmoil is emblematic of the film’s overall aesthetic—a collision of beauty and brutality, of the sublime and the profane. The music does not merely accompany the visuals; it amplifies them, adding an additional layer of emotional complexity to an already multifaceted narrative.

Subcultural Resonance: Buffalo ’66 as a Manifesto for the Marginalized

In the years since its release, Buffalo ’66 has transcended its indie origins to become a touchstone of subcultural significance—a film that resonates with those who exist on the fringes of society, who feel alienated from the mainstream and adrift in a sea of existential uncertainty. It is a film that speaks to the disaffected, the disenfranchised, and the disillusioned—a cinematic mirror held up to a generation that sees its own struggles reflected in Billy Brown’s tortured existence.

The film’s influence can be felt in the realm of fashion, where Gallo’s anti-aesthetic has been embraced as a form of rebellion against the sanitized, homogenized trends of the mainstream. Billy Brown’s sartorial choices—a mélange of thrift-store finds, oversized jackets, and scuffed boots—have become emblematic of a certain brand of disaffected cool, a rejection of the polished and the pristine in favor of the worn and the weathered. Christina Ricci’s Layla, with her wide-eyed innocence and retro-styled allure, embodies a subversive femininity that challenges conventional notions of beauty and desirability.

But beyond its surface-level influence, Buffalo ’66 resonates on a deeper, more philosophical level. It is a film that interrogates the very nature of identity, exploring the ways in which we construct and deconstruct ourselves in response to the expectations of others. Billy’s desperate attempts to project an image of normalcy—to convince his parents, and by extension himself, that he is a successful, well-adjusted individual—are ultimately futile, revealing the fragility of the self in a world that demands conformity and punishes deviation.

Forever ‘66

More than two decades after its release, Buffalo ’66 remains a seminal work of independent cinema, a film that defies easy categorization and continues to challenge, inspire, and provoke. Its legacy lies not only in its aesthetic and narrative innovations, but in its uncompromising exploration of the human condition—the existential angst, the yearning for connection, the struggle to find meaning in a world that often seems devoid of it.

Buffalo ’66 is not merely a film; it is a statement, a manifesto, a work of art that demands to be engaged with on multiple levels. It is a film that speaks to the disaffected and the marginalized, offering a voice to those who feel voiceless and a mirror to those who see themselves reflected in its fractured protagonist. In a cinematic landscape often dominated by the superficial and the ephemeral, Buffalo ’66 stands as a testament to the enduring power of personal, uncompromising storytelling—a film that, like its creator, refuses to conform, to compromise, or to be forgotten.

In the end, Buffalo ’66 is more than just a film; it is a cinematic odyssey, a journey into the heart of darkness that lies within us all, and a reminder that even in our most desolate moments, there is beauty to be found in the wreckage of our lives.