Gus Van Sant, a name that resonates profoundly within the realms of contemporary cinema, stands as an auteur who has ceaselessly pushed the boundaries of filmic expression. Renowned for his experimental approach, Van Sant has carved a niche where silence and length coalesce into a meditative exploration of human existence. His cinematic oeuvre, enriched by the influences of Chantal Akerman, Jean-Luc Godard, and Jonas Mekas, exhibits a profound dedication to the art of long shot sequences and an unparalleled commitment to unconventional storytelling.

In this retrospective, we delve into the intricacies of Van Sant’s work, dissecting his films with meticulous care, unraveling the threads of his passion for experimental cinema, and understanding his personal thoughts and commitments that shape his artistic vision. This journey through his filmography is not merely an analysis but a celebration of a filmmaker who has redefined the language of cinema.

The Early Years: Establishing a Unique Voice

Mala Noche (1986)

Van Sant’s debut feature, Mala Noche, serves as an audacious proclamation of his thematic and stylistic preoccupations. Adapted from Walt Curtis’s autobiographical novel, the film immerses the audience in a raw portrayal of unrequited love and the struggles of marginalized communities. Shot in black and white, Mala Noche echoes the gritty realism of Akerman’s work, while its fragmented narrative structure hints at the influence of Godard.

The film’s long takes and deliberate pacing allow the viewer to linger in the ephemeral moments of beauty and despair, establishing a motif that Van Sant would revisit throughout his career. Mala Noche is not merely a film but a testament to Van Sant’s willingness to confront uncomfortable truths with an unflinching gaze.

Drugstore Cowboy (1989)

With Drugstore Cowboy, Van Sant ventured into the world of addiction, crafting a narrative that oscillates between dark humor and poignant tragedy. The film’s depiction of a drug-addicted couple, portrayed by Matt Dillon and Kelly Lynch, unfolds with a rhythmic fluidity that mirrors the chaotic yet strangely ordered world of its protagonists.

Van Sant’s use of long shots in Drugstore Cowboy is both a stylistic choice and a narrative device, capturing the inexorable passage of time and the inescapability of the characters’ plight. The film’s experimental edge is further accentuated by its hallucinatory sequences, blurring the line between reality and illusion—a technique reminiscent of Mekas’s avant-garde sensibilities.

The 1990s: A Decade of Exploration

My Own Private Idaho (1991)

My Own Private Idaho stands as a magnum opus in Van Sant’s filmography, blending Shakespearean drama with the desolate beauty of the American Northwest. The film’s nonlinear narrative and fragmented storytelling pay homage to Godard’s revolutionary techniques, while its intimate portrayal of friendship and longing reflects Akerman’s influence.

River Phoenix and Keanu Reeves deliver performances that are hauntingly raw, their journey through the vast landscapes captured in lingering shots that emphasize the solitude and vulnerability of their characters. Van Sant’s use of long takes in My Own Private Idaho serves to amplify the emotional resonance, inviting the audience to experience the passage of time and the weight of unspoken words.

Even Cowgirls Get the Blues (1993)

In Even Cowgirls Get the Blues, Van Sant embraced a more whimsical and surreal approach, adapting Tom Robbins’s novel into a vibrant, albeit polarizing, cinematic experience. The film’s eclectic visual style and offbeat narrative are indicative of Van Sant’s willingness to experiment with form and content.

The use of long shots in Even Cowgirls Get the Blues is less pronounced, but Van Sant’s penchant for capturing moments of stillness amidst the chaos remains evident. The film’s reception was mixed, yet it stands as a testament to Van Sant’s unyielding commitment to artistic experimentation.

To Die For (1995)

To Die For marked a shift towards a more mainstream narrative, yet Van Sant’s distinctive voice remained undiluted. The film’s satirical take on media obsession and the pursuit of fame is conveyed through a series of mockumentary-style interviews and darkly comedic sequences.

Nicole Kidman’s portrayal of the ambitious and manipulative Suzanne Stone is rendered with chilling precision, and Van Sant’s direction ensures that each scene is imbued with a sense of impending doom. The long shots in To Die For are utilized sparingly but effectively, enhancing the tension and underscoring the absurdity of the characters’ actions.

Good Will Hunting (1997)

Good Will Hunting brought Van Sant widespread acclaim, with its heartfelt narrative and compelling performances by Matt Damon and Robin Williams. While the film adheres more closely to conventional storytelling, Van Sant’s influence is evident in its nuanced character development and the subtle, introspective moments that punctuate the narrative.

The long shots in Good Will Hunting are employed to great effect, capturing the contemplative silences and the profound connections between characters. Van Sant’s ability to balance emotional depth with visual storytelling is a testament to his maturation as a filmmaker.

The Early 2000s: Embracing Minimalism

Psycho (1998)

Van Sant’s shot-for-shot remake of Hitchcock’s Psycho was a bold and controversial endeavor. While the film was met with mixed reviews, it served as an exploration of cinematic form and the relationship between original and reproduction.

The use of long shots in Psycho is faithful to Hitchcock’s meticulous framing, yet Van Sant’s subtle deviations offer a fresh perspective on the classic thriller. This film stands as a curious anomaly in Van Sant’s oeuvre, a testament to his willingness to challenge both himself and his audience.

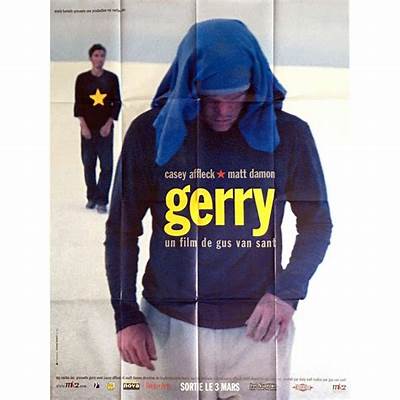

Gerry (2002)

Gerry marks a significant departure from Van Sant’s earlier works, embracing an austere minimalism that draws heavily from Akerman’s meditative style. The film’s plot is sparse, focusing on two friends, both named Gerry, who become lost in the desert. Van Sant’s use of extended long shots and minimal dialogue transforms the narrative into a contemplative exploration of human endurance and existential despair.

The barren landscapes and the protagonists’ aimless wandering evoke a sense of profound isolation, with the long takes emphasizing the relentless passage of time. Gerry is a cinematic poem, its beauty lying in its stark simplicity and the raw emotional truth it conveys.

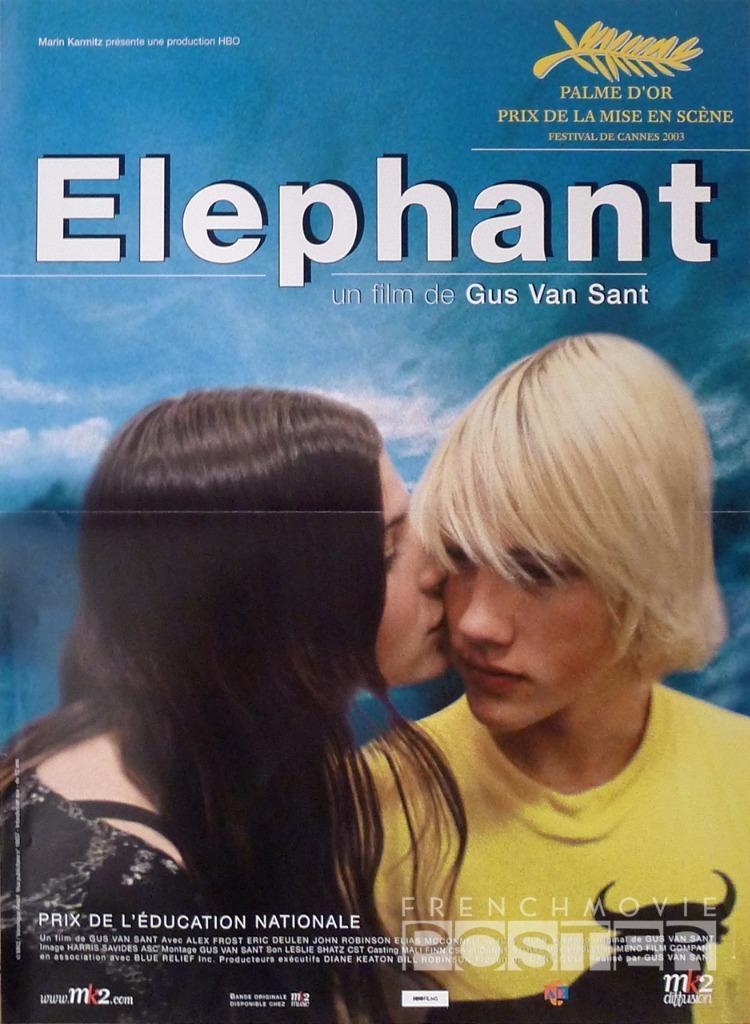

Elephant (2003)

Inspired by the Columbine High School massacre, Elephant is a harrowing examination of youth violence and the banality of evil. The film’s nonlinear narrative and detached observational style draw comparisons to Godard’s experimental techniques, while its long takes and emphasis on mundane details are reminiscent of Akerman’s approach.

Van Sant’s decision to use long, unbroken shots in Elephant serves to immerse the audience in the ordinary moments leading up to the horrific event, creating a sense of unease and inevitability. The film’s stark realism and haunting silence resonate deeply, making it one of Van Sant’s most powerful works.

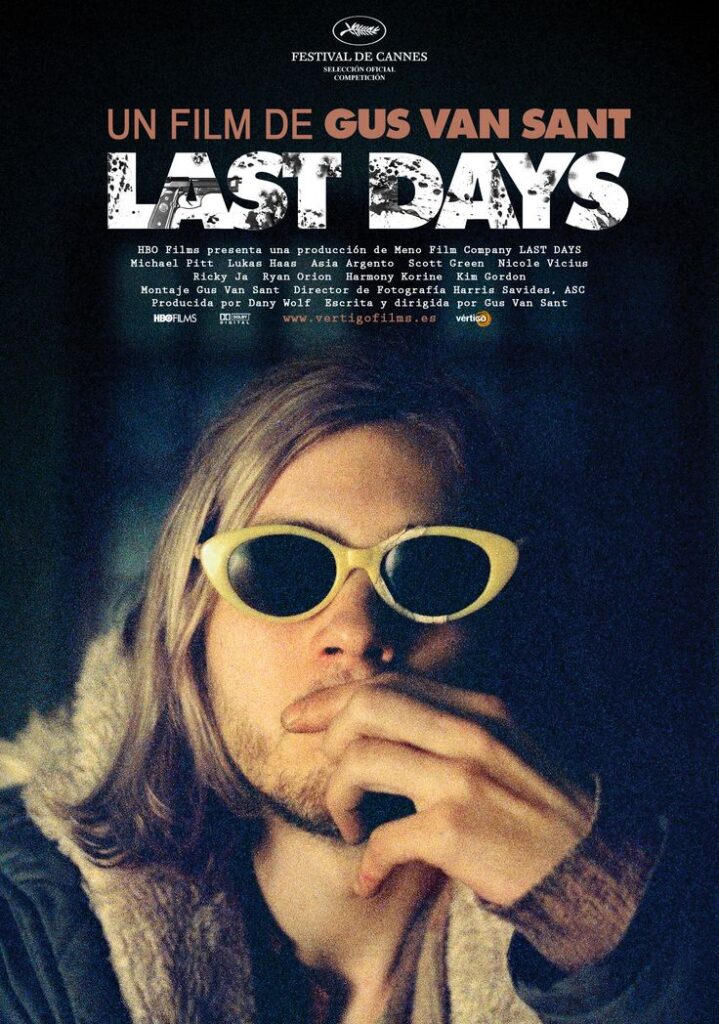

Last Days (2005)

In Last Days, Van Sant offers a fictionalized account of the final days of a rock musician, inspired by Kurt Cobain. The film’s languid pace and minimalist dialogue evoke a sense of melancholy and existential angst, capturing the protagonist’s descent into isolation and despair.

The long shots in Last Days are instrumental in conveying the protagonist’s detachment from reality, with the camera lingering on mundane actions and empty spaces. This deliberate pacing creates a contemplative atmosphere, allowing the viewer to experience the protagonist’s inner turmoil and the inexorable passage of time.

The Late 2000s: Experimentation and Reflection

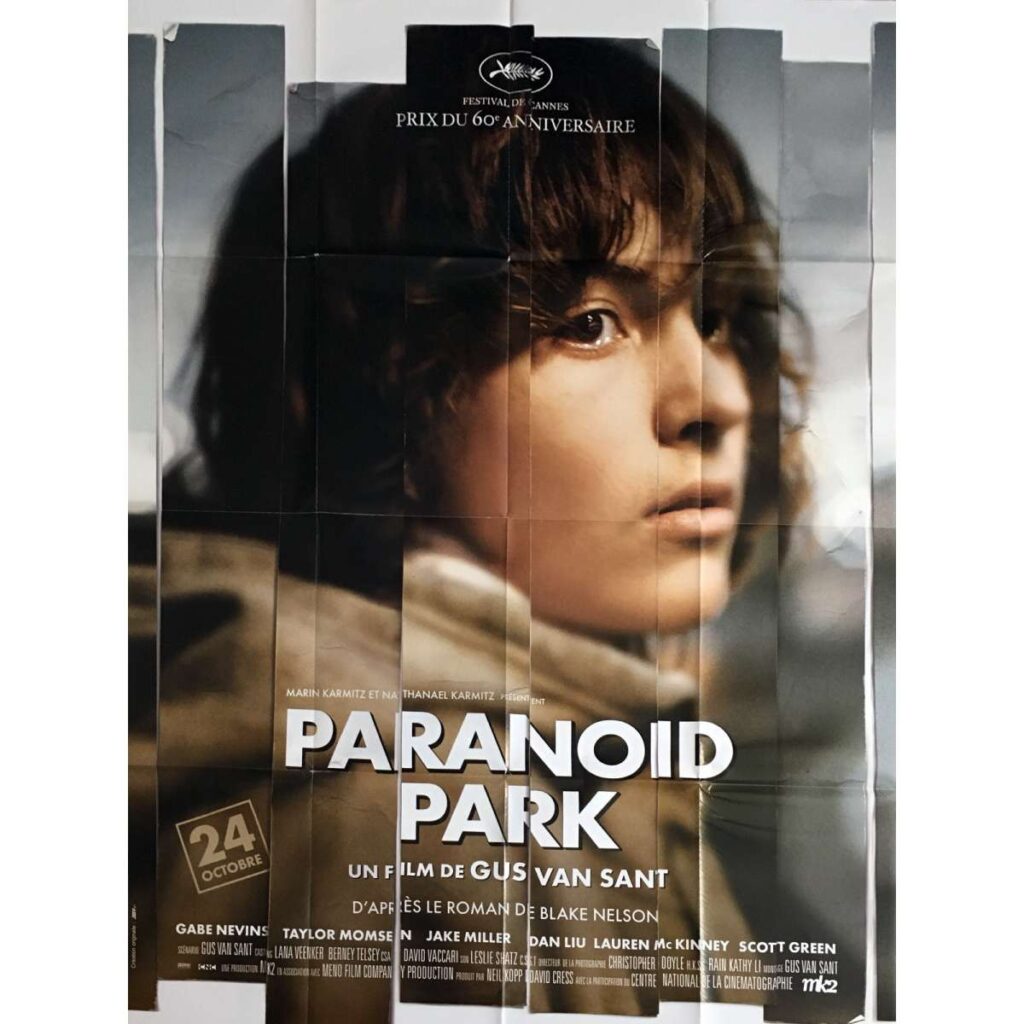

Paranoid Park (2007)

Paranoid Park explores the fractured psyche of a teenage skateboarder who inadvertently causes a tragic accident. The film’s nonlinear narrative and experimental visual style reflect Van Sant’s ongoing commitment to pushing the boundaries of conventional storytelling.

The use of long shots in Paranoid Park serves to emphasize the protagonist’s alienation and the weight of his guilt. Van Sant’s fluid camerawork and evocative use of silence create a dreamlike atmosphere, drawing the viewer into the protagonist’s disoriented mind. The film’s haunting beauty and emotional depth reaffirm Van Sant’s status as a master of experimental cinema.

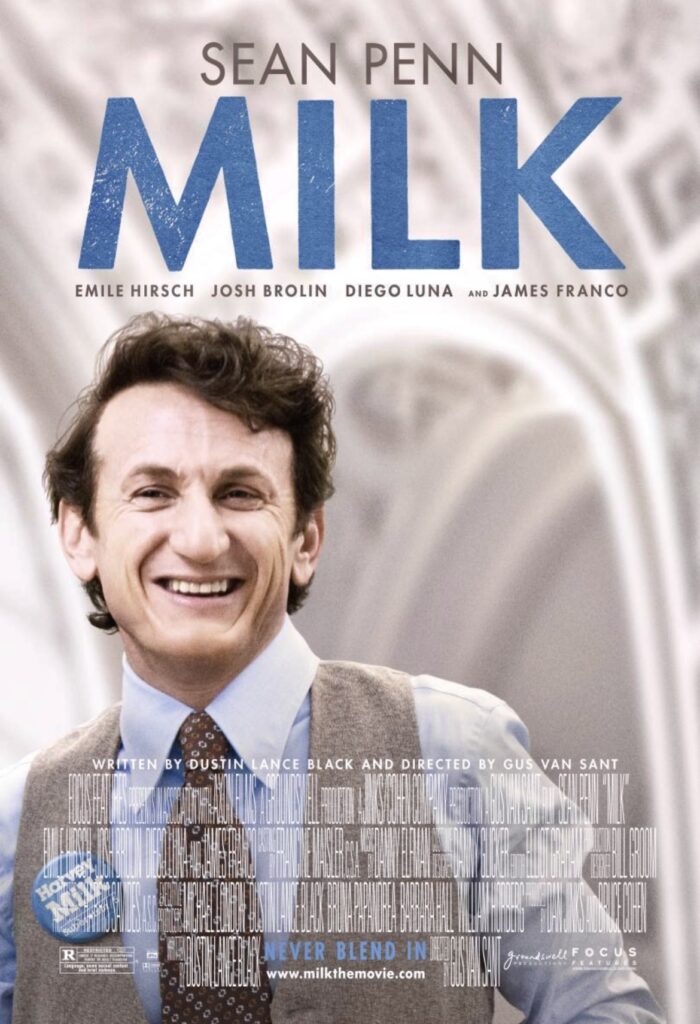

Milk (2008)

Milk is a departure from Van Sant’s more abstract works, presenting a biographical account of Harvey Milk, the first openly gay elected official in California. The film’s narrative structure is more conventional, yet Van Sant’s direction ensures that it remains a deeply personal and poignant portrayal of a pivotal figure in LGBTQ+ history.

The long shots in Milk are utilized to capture the intimacy and urgency of Milk’s political activism, as well as the broader social context of the era. Sean Penn’s powerful performance, coupled with Van Sant’s sensitive direction, results in a film that is both inspirational and profoundly moving.

The 2010s: A Return to Personal Cinema

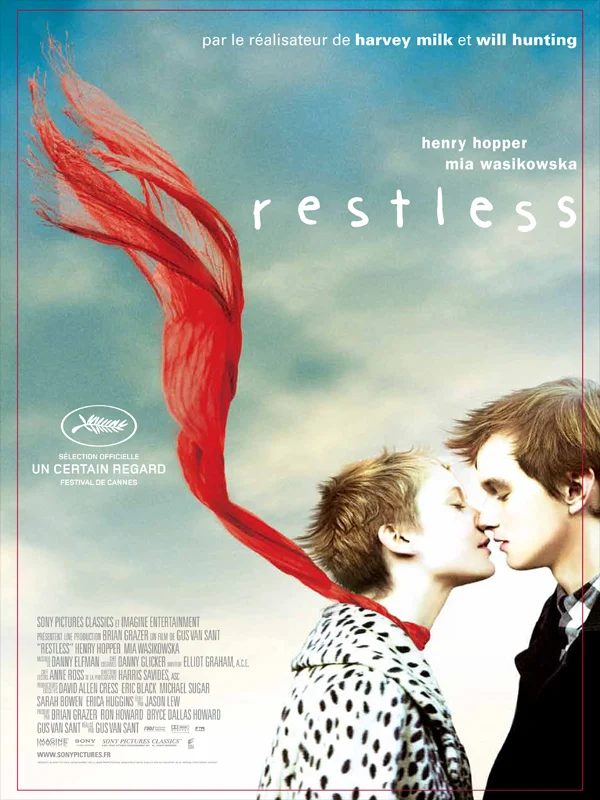

Restless (2011)

Restless is a tender exploration of young love and mortality, focusing on the relationship between a terminally ill girl and a funeral-obsessed boy. The film’s whimsical tone and delicate visual style reflect Van Sant’s softer, more introspective side.

The long shots in Restless capture the ephemeral beauty of the protagonists’ romance, emphasizing the fleeting nature of life and love. Van Sant’s gentle touch and poetic sensibility imbue the film with a sense of wonder and melancholy, making it a poignant addition to his body of work.

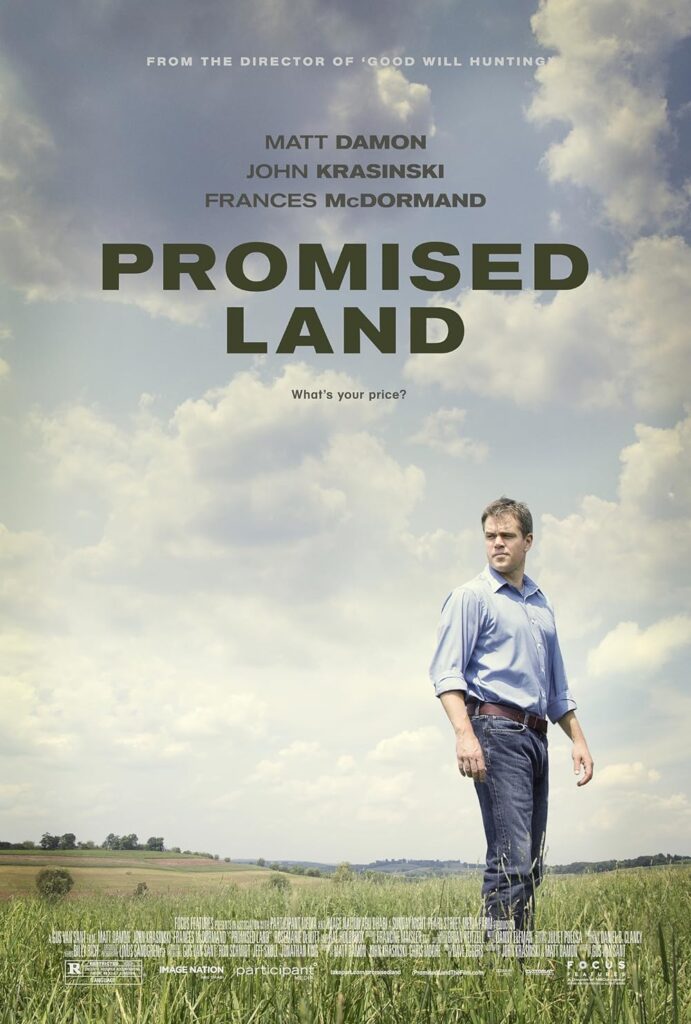

Promised Land (2012)

In Promised Land, Van Sant tackles the complex issues of environmentalism and corporate greed, presenting a nuanced portrayal of a small town divided by the prospect of natural gas drilling. The film’s narrative is grounded in realism, yet Van Sant’s direction ensures that it remains emotionally resonant and thought-provoking.

The long shots in Promised Land are employed to capture the expansive landscapes and the subtle dynamics of the community, emphasizing the interconnectedness of people and their environment. The film’s contemplative tone and social relevance highlight Van Sant’s continued commitment to addressing pressing contemporary issues.

The Sea of Trees (2015)

The Sea of Trees explores themes of grief and redemption, following the journey of an American man who travels to Japan’s Aokigahara Forest with the intention of ending his life. The film’s narrative structure and emotional depth reflect Van Sant’s mature sensibility and his ability to tackle profound existential questions.

The long shots in The Sea of Trees are used to capture the haunting beauty of the forest and the protagonist’s introspective journey. Van Sant’s direction creates a meditative atmosphere, allowing the viewer to engage deeply with the film’s themes of loss, forgiveness, and the search for meaning.

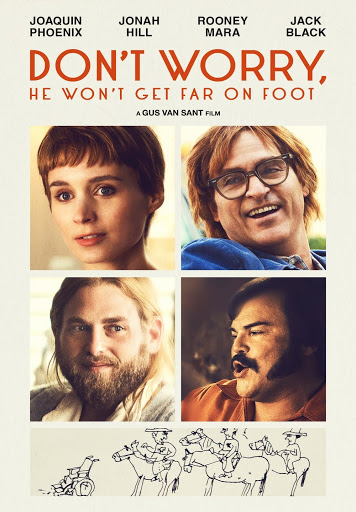

Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot (2018)

Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot is a biographical drama that chronicles the life of John Callahan, a quadriplegic cartoonist. The film’s narrative is interspersed with Callahan’s irreverent humor and his struggles with addiction and recovery.

Van Sant’s use of long shots in this film serves to capture the raw, unfiltered reality of Callahan’s life, highlighting both his vulnerabilities and his resilience. The film’s empathetic portrayal of disability and the transformative power of art underscores Van Sant’s ability to convey deep emotional truths with sensitivity and grace.

Influences and Inspirations

Chantal Akerman: The Art of Stillness

Chantal Akerman’s influence on Van Sant is profoundly evident in his use of long takes and his exploration of silence and stillness. Akerman’s ability to transform mundane actions into meditative experiences resonates deeply with Van Sant’s cinematic ethos. Her seminal work, Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, exemplifies this approach, and its impact on Van Sant is unmistakable.

Jean-Luc Godard: The Revolutionary Spirit

Jean-Luc Godard’s radical approach to narrative structure and his penchant for breaking cinematic conventions have left an indelible mark on Van Sant’s work. Godard’s influence is particularly evident in Van Sant’s fragmented storytelling and his willingness to experiment with form and content. Films like My Own Private Idaho and Elephant bear the hallmark of Godard’s revolutionary spirit.

Jonas Mekas: The Poetics of Everyday Life

Jonas Mekas’s avant-garde sensibilities and his focus on capturing the poetry of everyday life have profoundly influenced Van Sant’s artistic vision. Mekas’s experimental techniques and his dedication to portraying the ephemeral moments of existence resonate deeply with Van Sant’s cinematic style, as seen in films like Gerry and Paranoid Park.

Personal Thoughts and Commitments

Gus Van Sant’s personal thoughts and commitments are intricately woven into the fabric of his films. His dedication to exploring marginalized voices and uncharted emotional territories is a reflection of his deep empathy and his commitment to social justice. Van Sant’s films are not merely artistic endeavors but profound meditations on the human condition, imbued with a sense of compassion and a quest for truth.

Van Sant’s passion for long shot sequences and experimental cinema is not just a stylistic choice but a philosophical stance. By embracing silence and length, he invites the audience to engage in a deeper, more contemplative experience of cinema. His films are spaces for reflection, where the viewer is encouraged to linger in the moments of stillness and to find beauty in the mundane.

In The End

Gus Van Sant’s cinematic journey is a testament to his unwavering commitment to artistic exploration and his profound understanding of the human soul. His films, enriched by the influences of Akerman, Godard, and Mekas, stand as pillars of experimental cinema, challenging conventional narratives and offering a unique perspective on the world.

Van Sant’s passion for long shots, his mastery of silence and length, and his dedication to capturing the ephemeral moments of existence have solidified his place as a visionary auteur. As we reflect on his body of work, we are reminded of the transformative power of cinema and the enduring legacy of a filmmaker who dares to see the world differently.