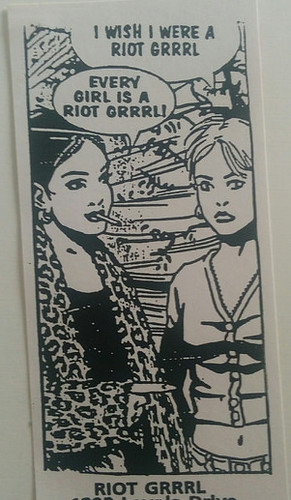

The Riot Grrrl movement, which emerged in the early 1990s, represents a significant chapter in the history of feminist punk. Originating primarily in the Pacific Northwest, particularly in Olympia, Washington, and extending to Washington D.C., this grassroots movement sought to confront and challenge the pervasive issues of mysoginy, body image, and abuse. It arose as a response to the marginalization of women in the punk scene and the broader societal context, aiming to create a space where women’s voices and experiences could be expressed and validated.

At its core, the Riot Grrrl movement embodied a DIY (Do-It-Yourself) ethic, emphasizing the importance of self-production and self-reliance. This ethos was evident in the creation of zines – self-published magazines that addressed feminist topics, shared personal stories, and provided information about the movement. These zines played a crucial role in disseminating the movement’s ideas and fostering a sense of community among its members. They also served as a platform for discussing critical issues such as body image, mental health, and violence, which were often ignored or misrepresented in mainstream media.

The impact of the Riot Grrrl movement extended beyond zine culture to significantly influence music and feminist discourse. Bands associated with the movement, including Bratmobile, Bikini Kill, and Heavens to Betsy, used their music as a tool for activism, addressing themes of empowerment, resistance, and solidarity. Their raw, unapologetic sound and powerful lyrics resonated with many, inspiring a new wave of feminist thought and action. The movement’s emphasis on inclusivity and intersectionality also encouraged a broader discussion about the diverse experiences of women, challenging the monolithic narratives often associated with feminism.

In essence, the Riot Grrrl movement was more than just a musical genre; it was a catalyst for social change. By advocating for gender equality and creating safe spaces for women’s expression, it left an indelible mark on both the punk scene and the feminist movement, laying the groundwork for future generations to continue the fight for justice and equality.

Key Figures and Bands in the Riot Grrrl Movement

The Riot Grrrl movement, which emerged in the early 1990s, was propelled by a constellation of influential figures and bands that sought to challenge the status quo through music, activism, and zine culture. Among the most prominent personalities was Kathleen Hanna, a pivotal figure whose work with the band Bikini Kill became synonymous with the movement. Hanna’s fierce lyrics and unapologetic stage presence spotlighted feminist issues, inspiring countless young women to find their voices.

Tobi Vail, another cornerstone of Bikini Kill, provided the rhythmic backbone for the band’s raw and energetic sound. Vail’s contributions extended beyond her drumming; she was instrumental in the creation of zines that articulated the principles of the Riot Grrrl ethos. These DIY publications served as a medium for sharing ideas, personal stories, and organizing grassroots activism.

Allison Wolfe, co-founder of Bratmobile, was another vital figure. Her collaboration with Molly Neuman in Bratmobile produced music that was both politically charged and accessible, resonating widely with the movement’s audience. Wolfe’s distinctive voice and candid lyrics helped Bratmobile carve out a unique space within the Riot Grrrl landscape.

Heavens to Betsy, featuring Corin Tucker, also played a significant role in shaping the movement. The band’s emotionally intense music addressed themes of gender oppression and personal empowerment, contributing to the broader discourse initiated by Riot Grrrl bands. Tucker’s later work with Sleater-Kinney continued to build on these foundations, cementing her status as a key figure in feminist punk rock.

Central to the Riot Grrrl movement was the creation and distribution of zines. These self-published works were not only a means of communication but also a form of resistance. Bands and activists used zines to share their thoughts, organize events, and build a community that transcended geographical boundaries. The collaborative nature of zine culture allowed for a multiplicity of voices and experiences to be represented, fostering a sense of solidarity among participants.

The synergy between these key figures and bands was instrumental in propelling the Riot Grrrl movement forward. Through their music and activism, they created a powerful platform for feminist discourse and action, leaving a lasting legacy on the cultural and political landscape.

Formation and Early Days of Bratmobile

Bratmobile, a pivotal band in the Riot Grrrl movement, was formed in 1991 by Allison Wolfe, Molly Neuman, and Erin Smith. The genesis of Bratmobile can be traced back to Wolfe and Neuman’s shared interests while attending the University of Oregon. Both were deeply influenced by the burgeoning punk rock scene and feminist literature, which served as the bedrock for their creative endeavors. The duo started collaborating on a feminist zine called “Girl Germs,” which laid the intellectual groundwork for what would become Bratmobile.

Erin Smith, who was then living in Washington, D.C., came into the fold through mutual connections in the punk community. The trio’s synergy was immediate, fueled by a common vision to challenge the male-dominated punk scene and address issues such as misogyny, misogyny, and female empowerment. Their music was raw and unapologetic, characterized by minimalist instrumentation and candid, often confrontational lyrics.

Their initial performances were marked by a DIY ethos, typical of the Riot Grrrl movement. Bratmobile’s early shows were often informal, taking place in basements, small clubs, and community centers. This grassroots approach not only made their music accessible but also fostered a sense of community and solidarity among young women. Their debut album, “Pottymouth,” released in 1993, encapsulated the spirit of their early work and quickly became an anthem for the Riot Grrrl movement.

Bratmobile’s role in the larger Riot Grrrl movement was significant. They were not just musicians but also activists who used their platform to advocate for social change. Their involvement went beyond music; they participated in organizing meetings, workshops, and protests, contributing to the movement’s broader goals. Through their relentless energy and commitment, Bratmobile helped to carve out a space for women in punk rock, laying the groundwork for future generations of female musicians and activists.

Bratmobile’s Musical Style and Themes

Bratmobile’s musical style is a distinctive fusion of punk rock energy and feminist themes, setting them apart within the Riot Grrrl movement. Their raw, unpolished sound captures the rebellious spirit of punk while delivering potent messages about gender inequality, female empowerment, and societal expectations. The band’s music often features fast tempos, minimalistic instrumentation, and a gritty, DIY aesthetic, which resonate strongly with the core principles of punk rock.

Their lyrics are a bold and unflinching commentary on the challenges faced by women in a patriarchal society. Songs like “Panik” and “Cool Schmool” highlight issues such as objectification, double standards, and the struggle for autonomy. By addressing these themes head-on, Bratmobile not only provided a voice for feminist concerns but also inspired a generation of women to challenge societal norms.

Comparatively, Bratmobile’s style shares similarities with other bands in the Riot Grrrl movement, such as Bikini Kill and Heavens to Betsy. However, Bratmobile’s approach is often seen as more playful and irreverent, incorporating elements of sarcasm and wit into their music. This unique blend of humor and activism helped them carve out a distinct niche within the movement.

What sets Bratmobile apart is their ability to balance raw musical aggression with insightful commentary. Their energetic performances and unapologetic stance on feminist issues made them a pivotal influence in the Riot Grrrl movement. The band’s willingness to confront taboo topics and challenge the status quo remains a defining characteristic of their legacy.

Bratmobile’s contribution to the Riot Grrrl movement is undeniably significant. Through their music, they not only entertained but also educated and empowered listeners, leaving an indelible mark on the landscape of punk rock and feminist discourse.

Bratmobile’s impact on the Riot Grrrl movement and the broader music scene is substantial and enduring. Emerging in the early 1990s, Bratmobile became a pioneering force within the Riot Grrrl movement, using their music and activism to challenge the status quo of the male-dominated punk scene. Their raw, unapologetic sound and feminist lyrics resonated with many, inspiring a wave of female musicians and bands to assert their presence in the music industry.

Bratmobile’s influence extended beyond their music. They were instrumental in spreading feminist ideas and encouraging discourse on issues such as gender inequality, body autonomy, and harassment. Through their zines, performances, and public statements, they created a platform for women to voice their experiences and demand change. This activism was not only pivotal in shaping the Riot Grrrl movement but also in fostering a sense of community and solidarity among women in punk and alternative music scenes.

Moreover, Bratmobile’s impact can still be observed in contemporary music and feminist movements. Many modern female artists and bands cite Bratmobile and the Riot Grrrl movement as significant influences on their work. The DIY ethos and feminist principles that Bratmobile championed continue to inspire musicians to explore themes of empowerment and resistance in their art. Additionally, the band’s legacy is evident in the ongoing conversations about gender and representation in the music industry, as well as in the continued efforts to create inclusive spaces for women and marginalized groups.

In summary, Bratmobile’s contributions to the Riot Grrrl movement and their broader impact on the music scene are profound. They not only helped to redefine the role of women in punk music but also laid the groundwork for future generations of female musicians and activists. The band’s enduring legacy is a testament to their pioneering spirit and the lasting power of their message.

Bratmobile’s Legacy and Reunions

Bratmobile’s influence extends far beyond their discography, resonating deeply within the realms of music and feminist activism. Emerging as a pivotal force in the early 1990s, their raw sound and unabashedly feminist lyrics carved out a unique space in the punk scene. However, the band’s journey was not without its interruptions. In 1994, Bratmobile disbanded, citing internal pressures and the inherent challenges of maintaining a band rooted in such a fiercely DIY ethos.

In 1999, Bratmobile reunited, reigniting the spark that had initially set them apart. This reunion was marked by the release of new music and live performances that reaffirmed their relevance and undiminished energy. Their return was not merely a nostalgic act but a reassertion of their commitment to the principles that had always defined them—empowerment, authenticity, and resistance against mainstream conventions.

Their subsequent activities included the release of the album “Ladies, Women and Girls” in 2000, which was met with critical acclaim for its potent blend of punk aggression and feminist themes. This period also saw Bratmobile engaging in various feminist causes, further cementing their status as icons of the Riot Grrrl movement.

Bratmobile’s legacy is evident in how their music continues to inspire new generations of artists and activists. Their influence can be traced in the work of contemporary punk bands and the renewed vigor of feminist movements. The band’s place in the history of the Riot Grrrl movement is irrefutable; they not only contributed significantly to its soundtrack but also embodied its ethos through their actions and artistic outputs.

Today’s musicians and activists draw from Bratmobile’s pioneering approach, finding in their legacy a source of inspiration and a call to action. As such, Bratmobile remains a vital reference point in discussions about the intersection of music and feminist activism, illustrating the enduring power of the Riot Grrrl movement.

Conclusion and Reflections on the Riot Grrrl Movement

The Riot Grrrl movement, emerging in the early 1990s, was a pivotal force in advancing feminist ideas through the lens of punk rock. Central to this movement were bands like Bratmobile, whose raw and unapologetic music resonated with a generation seeking to challenge the status quo. Bratmobile, alongside other key bands, provided a powerful voice for young women, addressing issues of mysogyny, body image, and female empowerment in a way that was both accessible and revolutionary.

Throughout this blog post, we have delved into the origins of the Riot Grrrl movement, tracing its roots back to the underground punk scene and highlighting its core philosophies. We examined how Bratmobile, with their energetic performances and provocative lyrics, encapsulated the spirit of Riot Grrrl. Their contributions were not just musical but also ideological, as they pushed for greater inclusivity and representation within the punk community and beyond.

The significance of the Riot Grrrl movement extends beyond its music. It created a cultural shift, inspiring countless young women to express themselves unapologetically and to demand equality. The zines, meetings, and networks established by Riot Grrrls fostered a sense of community and solidarity that transcended geographical boundaries. This movement laid the groundwork for future feminist endeavors and has left an indelible mark on the cultural landscape.

In today’s society, the legacy of the Riot Grrrl movement remains relevant. As we continue to grapple with issues of gender inequality and representation, the lessons and ethos of Riot Grrrl resonate profoundly. Bands like Bratmobile remind us of the power of music as a tool for social change and the importance of creating spaces where marginalized voices can be heard.

We encourage readers to explore more about the Riot Grrrl movement and its music. Understanding this movement’s history not only provides insight into a significant cultural phenomenon but also inspires continued advocacy for feminist ideals. The spirit of Riot Grrrl lives on, urging us to challenge norms and strive for a more just and equitable society.

An Interview With Allison Wolfe

I did this interview with Allison Wolfe on October 11th 2011, it is still to this day one of the most important and meaningful interviews I have done. As I made the decision to continue my feminist content and culture promotion through magazines, I felt like it was an essential part of the work to resurface this incredible interview retracing the important visions of a true riot grrrl pioneer and amazing artist.

1. What is your very own definition of “Riot Grrrl”?

I think of riot grrrl as a part/strain of third-wave feminism that was about making punk rock scenes more feminist, while also making (academic) feminism more punk rock. The idea was to forge a consciously politicized connection between punk rock (alternative youth) culture and a feminism that spoke plainly and directly to the reality of our lives. We embraced a D.I.Y. (do-it-yourself) approach to making our voices heard, taking over the means of production to provide a platform to challenge dominant culture.

I tend to see riot grrrl as feminist cultural activism pertaining to a certain era, the early ‘90s (mostly) American independent music scene.

2. According to you, who founded the Riot Grrrl movement?

Mostly Kathleen Hanna, me, Molly Neuman, and Tobi Vail really had the initial supportive conversations and community-building that led to the creation of riot grrrl. Of course many other girls got involved after that and led it in various directions. We always meant to keep it open and up to interpretation by any girls who embraced it.

3. How were the Riot Grrrl years? Do you miss them?

I have so many precious memories of those years: exciting, fun and painful. We were in our early ‘20s and thought we could change the world! And why not? Struggle exists as long as injustice does… It was exhilarating and confrontational. The sharing of alternative resources, social-political ideas and deeply personal stories, as well as the D.I.Y. support systems and net-working, was crucial to that era. Everything was about identity politics then, so sometimes things got too personal, rigid or narrow in scope. I really miss that community and support network of punky-feminist girls and like-minded boys. I think it’s important for marginalized people to not feel alone. But we all end up spread out across the country or world, still doing creative or politicized things, but maybe now alone in our own bedrooms.

4. Do you feel like Riot Grrrl is still alive?

It’s hard to say. I’m not against the use of the term “riot grrrl” by girls today, but I tend to see it as part of a certain time and place, an era. I also see it as a type of feminism, even if from the early ‘90s third wave, that should be acknowledged as such and not just some “fad.” As long as misogyny continues to exist, so must feminism, in many forms.

5. How about the riot grrrl scene in music, is it still alive?

Well, I still play in bands, and I’m associated with riot grrrl. So if my band plays somewhere, people might call it “riot grrrl,” for lack of a better term or imagination. But I don’t reject it. I’m proud of my past. The odd thing is that now there seems to be a lot of riot grrrl revivalism, as it’s been 20 years since it began. I appreciate the sentiment, but sometimes within the retrospective activities, younger people only embrace the style or music, or their idea of it. I wish that some of the younger people trying to recreate riot grrrl themes would actually reach out and engage with the active women of that era and their political ideas.

6. What did you think about the Riot Grrrl manifesto? Is this a text you respected and still respect? How did the idea of the zine “Girl Germs” come to you? How did you start it?

Kathleen Hanna wrote the riot grrrl manifesto. I think it was brilliant and revolutionary, really. For girls, still words to live by, I think.

Girl Germs was created by Molly Neuman and I while we were at the University of Oregon. We were inspired by people like Tobi Vail, Donna Dresch, Kathleen Hanna, other punk music girls. We knew we wanted to do something. At first, we wanted to do an all-female-programmed radio show, but our university had no college radio at the time. So Tobi suggested we do a ‘zine. We just wanted a forum to talk about girl bands and cool things going on. We wanted to engage with other like-minded people, and since it was pre-internet, making a ‘zine seemed like the best way to do that. I came up with the title “Girl Germs,” based on the observation that “girly” things get devalued in our society from an early age, and that a new feminism could embrace and uplift those things, rather than promoting that girls should be more like boys to get respect in society.

7. What were the differences between Bratmobile and Cold Cold Hearts to you? Do you still have this same strength, this very particular way of fighting for feminism?

Bratmobile was my first band, based in Olympia, Washington, and Washington DC, and Cold Cold Hearts was my second “real” band. I was in a project band with some people in Olympia called “Dig Yr. Grave” for a bit before Cold Cold Hearts. Bratmobile was basically me, Erin Smith on guitar, and Molly Neuman on drums. Erin and I started Cold Cold Hearts in Washington DC about a year after Bratmobile broke up. There were two other girls in the final version of CCH, Nattles (later in Flin Flon) and Katherine Brown. Bratmobile has been my most popular band, but I prefer the Cold Cold Hearts recordings. My lyrics for CCH came more fast and furious, I sound completely insane! Cold Cold Hearts was probably my favorite band musically that I’ve been in, but the worst as far as friendship and functionality were concerned.

I see my music, performance and persona as being engaged in feminist cultural activism, with a focus on female self-esteem issues and how the personal is political.

8. What does “feminism” mean to you? You are a big part of third-wave feminism, how do you feel that you have contributed to it?

Feminism is the insistence of the value of women in society and a politically conscious struggle against patriarchy, which systemically devalues women. It is essential to the survival of women in a misogynist world.

I am happy to have been a part of a strain of third wave feminism in my own way. I believe I have contributed in more of a cultural activist way, by getting my feminist ideas out there creatively. I sing and talk mostly about the devaluation of women in daily life, about female self-esteem issues, and how the personal is political.

9. Can you tell me your best memories with Bratmobile and the true story of the band?

Bratmobile was my first band. The drummer Molly Neuman and I met in the dormitory at the University of Oregon in 1989, and we were pretty bored of the predominately hippie scene in Eugene, Oregon. We were pretty politicized and restless, and very influenced by the Olympia music scene, and started hanging out and networking more with girls up there in my hometown. Calvin Johnson asked us to play a show on Valentine’s Day, 1991, up in Olympia, opening for Bikini Kill (their 3rd show) and Some Velvet Sidewalk. We didn’t yet consider ourselves a “real” band, and realized we’d better figure out how to write songs and play something quick. It worked out pretty good and we were very much supported and encouraged by the Olympia music scene. We ended up spending more and more time in Washington DC later, because Molly’s from there, and connected with Erin Smith who then started playing guitar with us. In the beginning, we had some other people play in Bratmobile a bit, like Christina Billotte (Autoclave, Slant 6, Quixotic) and Jen Smith (the Quails, helped create the term “riot grrr”).

There are so many memories of Bratmobile, I wouldn’t even know where to start…

10. One artist is deeply involved in the Riot Grrrl movement: Kathleen Hanna. What do you think about her works and creations concerning feminism and Riot Grrrl?

Kathleen is a true visionary. I’ve never met anyone else quite like her. She has endless amounts of passion and drive. I used to wonder if her wheels ever stopped turning, if she ever slept at night! She’s brilliant, prolific and well-spoken. But she can also be pretty funny. I think a lot of people don’t realize that.

11. Who are your main influences? (in music, cinema, politics and so on)

My most significant influence was my mother, Pat Shively. She was a lesbian feminist activist who started the first women’s health clinic in Olympia, Washington. She provided sensitive feminist health care for women, by women. She was outspoken and funny and dealt courageously with a lot of obstacles and controversy in her life.

Music: Kathleen Hanna, Kat Bjelland/Babes in Toyland, the Slits, Beat Happening, Bow Wow Wow, Dolly Parton, Johnny Cash.

Art: Ana Mendieta

Writers/thinkers/speakers: Amy Tan, Margaret Cho, Roseanne Barr, Alice Walker, bell hooks, Dorothy Allison, Ralph Nader

Film: Michael Moore, Margarethe von Trotta

12. You initiated Ladyfest, a huge deal for us activist women! Can you tell us a bit more about the initiation of this project and its history?

In 1999, Bratmobile had already reformed, and the Experience Music Project was trying to get some riot grrrls together for a retrospective to put in their new museum in Seattle. I helped get people together and the interviews took place in Olympia, Washington. It was the first time in years that many of us former riot grrrls really talked about our experiences with riot grrrl and felt validated for what we’d achieved. It felt good, but made me realize how much I missed being part of a politicized community (like riot grrrl), how there were still all these amazing women and girls doing creative and politicized stuff but kind of all separately in our own spaces, with no real collective consciousness anymore.

It was also hard to just see how bad the “alternative” music scene had become by the late ‘90s, so anti-politicized, backlash, misogyny. A friend of mine from Lookout! Records, Tristin Laughter, had recently written an article about how misogynyst and mainstream music festivals like Warped Tour were, and it made me realize, wait, we can’t just sit here and complain about how our punk culture gets stolen, mutated, and sold back to us at a high price for passive consumption. We need to be full participants in our own communities, which includes creativity, entertainment, etc.

So that’s what got me thinking up the idea of Ladyfest. I knew Olympia in 2000 would be the perfect time and place for such an event. Olympia has a history of strong women running things and has affordable access to space, and people are pretty open and progressive there, and help each other out in a small town setting. And I thought the new millennium would be the right time to try to propose a progressive, politicized way of experiencing music and culture, as opposed to all the garbage surrounding us.

I knew in the Pacific Northwest there were so many awesome feminists in the music scene who could make it happen, and there would be more accessible resources than many other places, bigger cities, etc.

Since then, Ladyfest has happened in so many places around the world.

They’ve all been unique and amazing, and brought communities of punky feminists together to create something inspiring and interesting, which is rare to see in general rock shows, parties, fests.

I’ve also been inspired by the bonds created during Ladyfests that continue after, the organizations that these feminists continue on with in their lives and communities.

13. Who are, according to you, the present artists who are the most involved in feminism?

Many, I’m sure, that I don’t even know about or might forget to mention… Wanda Sykes, Margaret Cho, Beth Ditto, Dynasty Handbag, Sharon Cheslow, Teri Suarez/Les Butcherettes, M.E.N., Rachel Carnes, Anna Joy Springer, Bridget Irish, Francois Cactus, Peaches, Kara Walker, Corin Tucker, Carrie Brownstein, Miranda July, Mira Billotte/White Magic, Ana da Silva/Raincoats, Patty Schemel. Arlene Textaqueen

14. I have always been very involved in the Riot Grrrl movement, you were and still are a huge inspiration for me, not to say a foundation. What are your projects for the future and what are you working on right now?

I currently live in Los Angeles. I work as a teacher of ESL/EFL (English as a Foreign Language) and play in a 4-girl band called “Cool Moms.”

I plan to work on a riot grrrl photo book with punk photographer Pat Graham, as well as an oral history book of riot grrrl.

15. Do you believe in a positive future for feminism?

Sure, why not? Don’t we have to?!