Robert Mapplethorpe (1946–1989) was an American photographer whose work exists at the intersection of provocation and beauty, capturing a tension that has left an indelible mark on contemporary art. His black-and-white portraits, still lifes, and nudes are immediately recognizable, noted for their stark precision, sensuality, and exploration of human identity. Known for pushing boundaries, particularly in terms of sexual expression, Mapplethorpe’s photographs also embody a classical aesthetic reminiscent of Renaissance art. His works delve into the core of the human experience, confronting viewers with the often taboo nature of sexuality, identity, and power.

But to understand Mapplethorpe fully is to recognize that his art cannot be separated from the cultural and social milieu that surrounded him, particularly the New York City of the 1970s and 1980s. It was a time of cultural upheaval, marked by the emergence of punk rock, the queer liberation movement, and the rise of AIDS. It was also the era of Patti Smith, the artist, and poet who shared a close relationship with Mapplethorpe, which profoundly influenced his artistic journey.

In exploring the art of Robert Mapplethorpe, we must not only dissect his technical mastery and themes but also contextualize his work within the broader framework of the New York art scene, his deep personal relationships, particularly with Patti Smith, and the cultural dialogues of the time.

The Early Years: Formative Influences and the Call to Art

Born in Queens, New York, Robert Mapplethorpe grew up in a conservative Catholic family, where he was deeply influenced by the iconography of the Church. This exposure to religious imagery would later resurface in his work, lending his photographs a sense of reverence, symmetry, and idealized form. Yet, alongside this piety was a desire to rebel. As a young man, he enrolled in the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn to study graphic design, though he never formally graduated. His artistic influences at this stage were broad, ranging from Renaissance masters like Michelangelo to contemporary pop artists like Andy Warhol.

Mapplethorpe’s earliest works were not photographs but collages. He worked with mixed media, cutting out images from pornographic magazines and juxtaposing them with more classical art forms, hinting at the duality that would characterize his future works. This early experimentation with form, content, and taboo themes set the foundation for his later photographic explorations.

In the early 1970s, photography became his primary medium. Armed with a Polaroid camera, Mapplethorpe started capturing his immediate surroundings, friends, and lovers in intimate, unvarnished moments. These early photographs were raw and unpolished but revealed a fascination with the human body, form, and identity that would persist throughout his career.

Patti Smith: A Muse, a Mirror, and a Soulmate

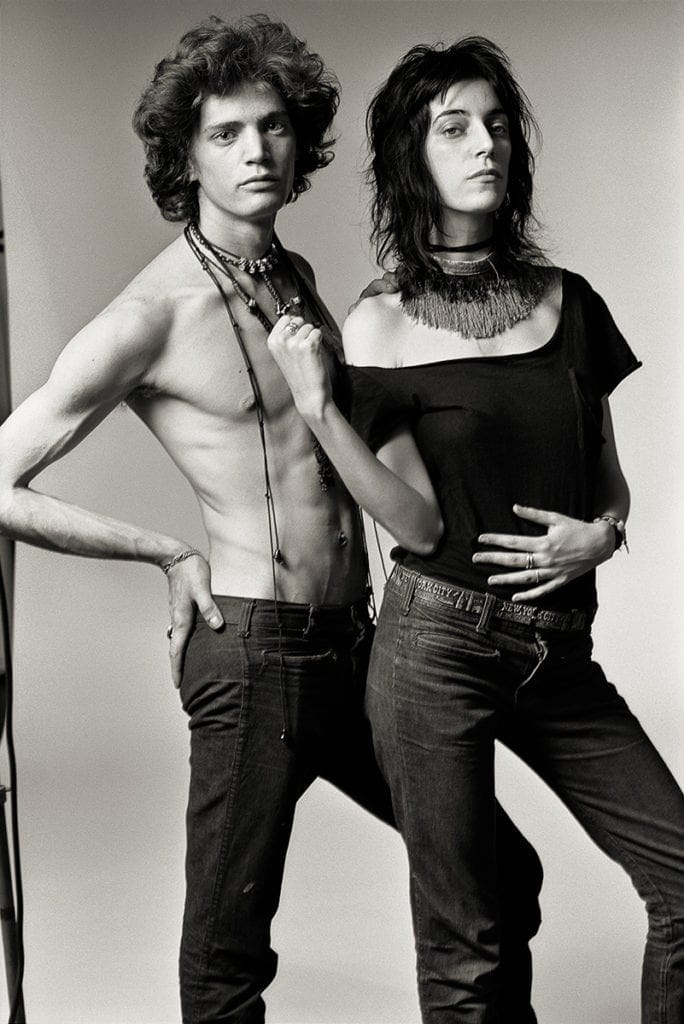

At the heart of Mapplethorpe’s personal and artistic development was his relationship with Patti Smith, the musician and poet who shared his passion for art and rebellion. The two met in 1967 when both were living at the Chelsea Hotel, a haven for artists, musicians, and bohemians. Their relationship, initially romantic, evolved into a deep friendship and artistic partnership that lasted until Mapplethorpe’s death in 1989.

Smith, in her memoir Just Kids, provides a vivid portrait of their bond, describing Mapplethorpe as both a mirror and muse. She recounts how they pushed each other artistically, living on the fringes of society and sharing an intense desire to break free from traditional norms. In many ways, Patti Smith was both the subject of Mapplethorpe’s art and its greatest champion. Her androgynous beauty, captured in one of his most iconic photographs for the cover of her album Horses (1975), reflects Mapplethorpe’s fascination with gender fluidity and the blurring of boundaries between male and female, strength and vulnerability.

Smith, with her raw, poetic lyricism and punk aesthetic, mirrored Mapplethorpe’s desire to subvert conventional expectations. Both artists were concerned with authenticity, yet they were equally invested in creating a mythos around their work. For Mapplethorpe, the camera was not just a tool for documentation but for transformation, a way to impose a sense of order and beauty onto the chaos of the world around him.

Their shared experiences in the burgeoning New York art scene played a significant role in shaping Mapplethorpe’s art. The city, with its vibrant mix of cultures, art movements, and underground subcultures, provided fertile ground for Mapplethorpe’s explorations of identity, sexuality, and power. It was a place where boundaries were constantly being tested, and Mapplethorpe thrived in this environment, surrounded by artists, musicians, and intellectuals who were similarly committed to pushing the limits of what was considered acceptable.

The New York Art Scene: A Nexus of Subversion and Experimentation

The 1970s and 1980s in New York were a period of intense cultural and social experimentation. The city was a melting pot of artists, musicians, and activists, and it was in this context that Mapplethorpe’s work flourished. It was an era defined by the rise of punk rock, the sexual revolution, and the burgeoning LGBTQ+ rights movement, all of which found expression in Mapplethorpe’s art.

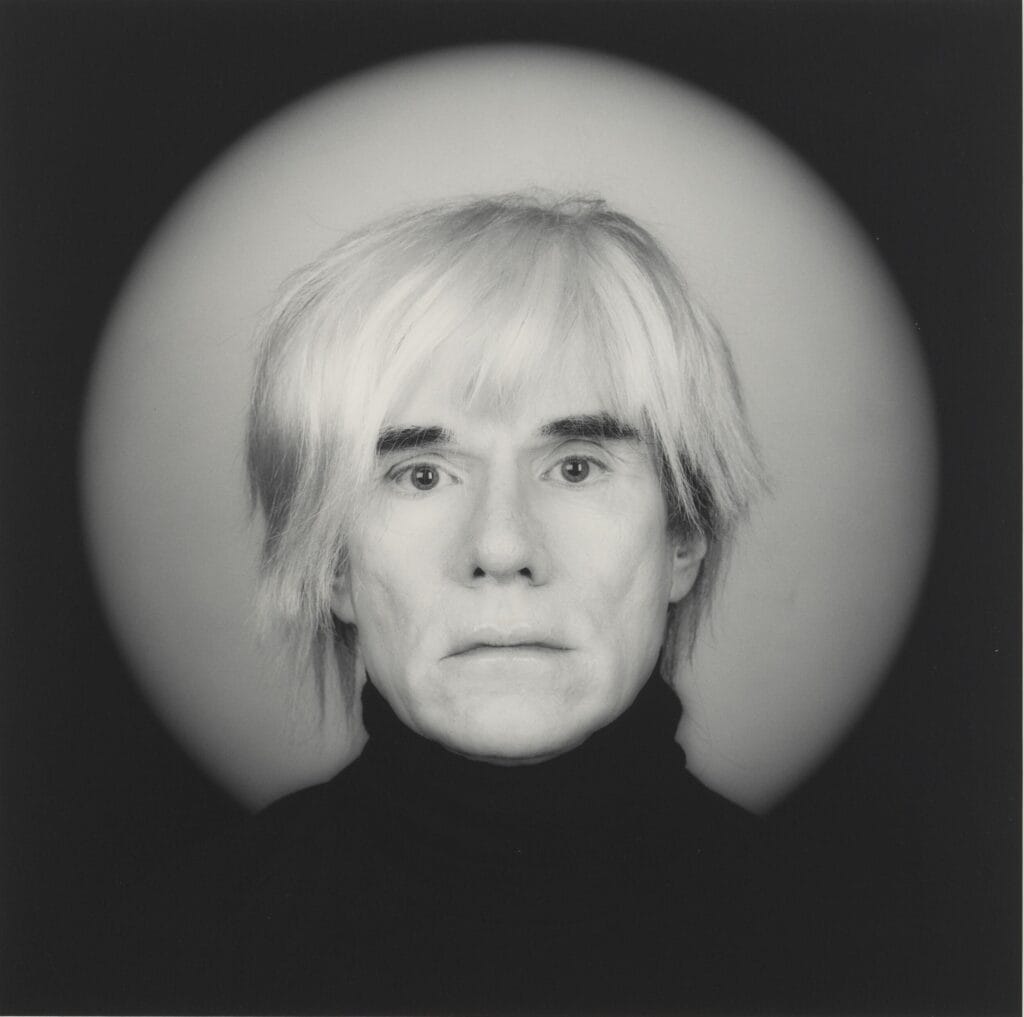

The downtown New York art scene, centered around galleries like the Robert Miller Gallery and spaces like the Chelsea Hotel, was marked by a desire to challenge traditional notions of art, beauty, and identity. Artists like Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, and Jean-Michel Basquiat were Mapplethorpe’s contemporaries, and their work, like his, often reflected the gritty, raw energy of the city. Warhol’s exploration of celebrity culture and consumerism, Haring’s vibrant graffiti art, and Basquiat’s street-influenced paintings all contributed to a cultural landscape that encouraged bold, provocative expression.

Mapplethorpe, however, was not interested in the ephemeral or the disposable. His work was rooted in a classical sense of beauty and form, but with a distinctly modern edge. His portraits of celebrities like Debbie Harry, Andy Warhol, and Grace Jones captured not just their physical appearance but their personas, turning them into modern-day icons. Yet, alongside these glamorous images were his more controversial works—photographs that explored the darker, more transgressive aspects of human sexuality.

Mapplethorpe’s X Portfolio, a series of explicit photographs depicting gay BDSM subcultures, remains one of his most polarizing bodies of work. These images, shot with the same care and precision as his more traditional portraits, confront viewers with a world that was, at the time, hidden from mainstream society. But rather than presenting these scenes as purely sensational or shocking, Mapplethorpe imbues them with a sense of dignity and beauty, challenging the viewer to reconsider their preconceived notions of morality and art.

In doing so, Mapplethorpe was not only pushing the boundaries of what could be shown in art galleries but also forcing a conversation about the role of the artist in society. Was it the artist’s responsibility to reflect the world as it was, or to push it in new directions? For Mapplethorpe, the answer was clear. His art was a tool for both self-expression and social commentary, a way to challenge conventional notions of beauty, identity, and desire.

Beauty, Sexuality, and Power: The Core Themes

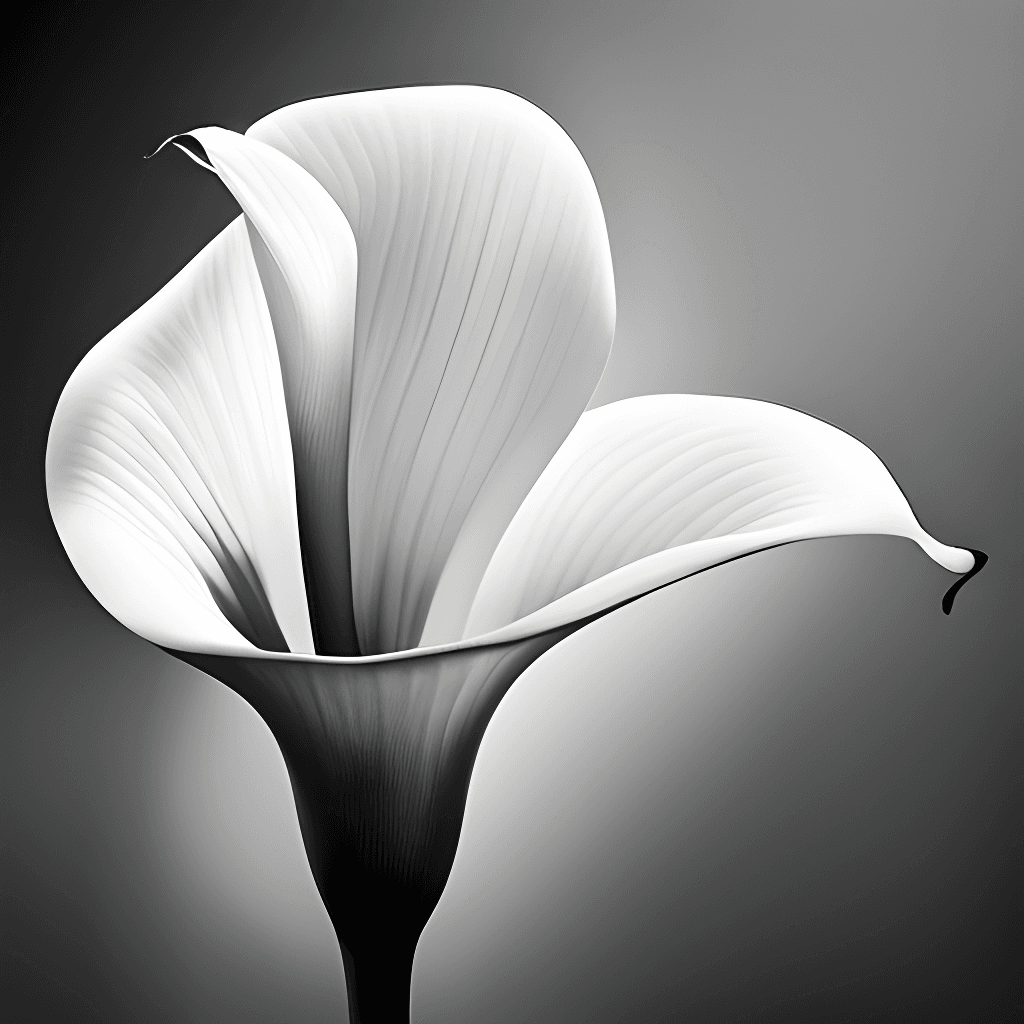

At the heart of Robert Mapplethorpe’s art is a profound exploration of the relationships between beauty, sexuality, and power. These themes are interwoven throughout his body of work, from his classical still lifes of flowers to his explicit depictions of BDSM practices. In every photograph, whether of a delicate orchid or a muscular nude, Mapplethorpe is concerned with capturing the essence of his subject and presenting it in a way that challenges the viewer’s assumptions.

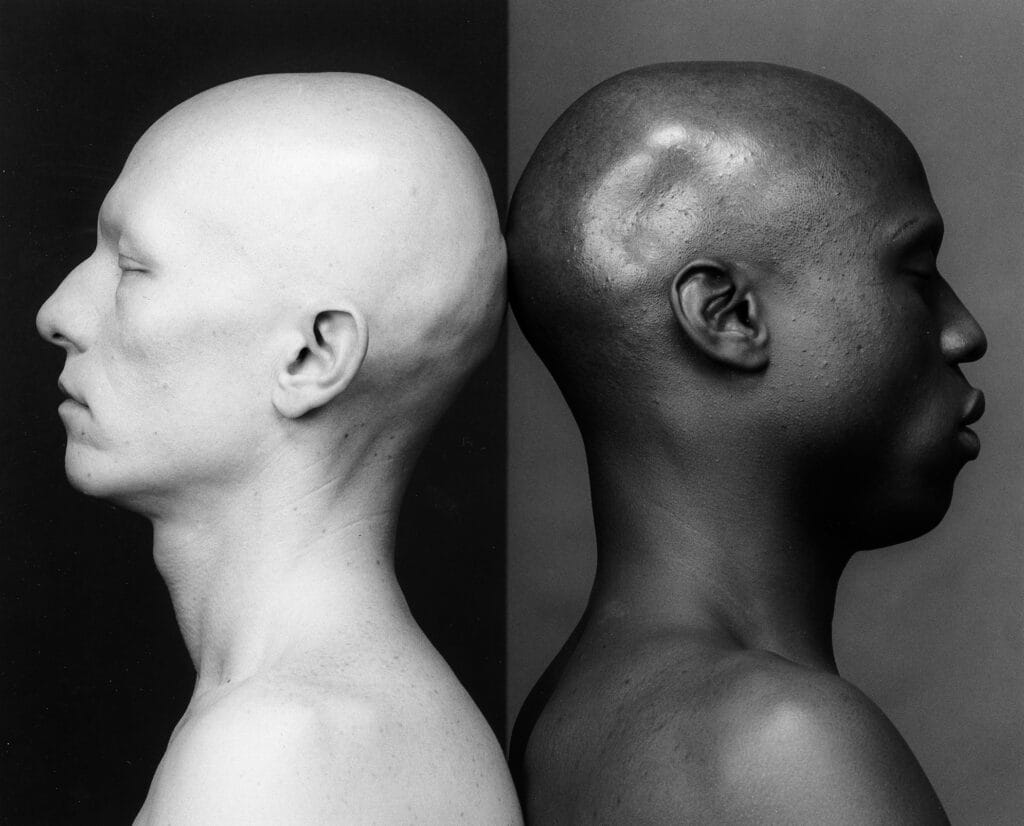

One of the most striking aspects of Mapplethorpe’s work is his ability to take subjects that are traditionally considered taboo or marginal and present them with a level of artistry and refinement that elevates them to the realm of high art. His photographs of black male nudes, for example, confront the racial and sexual stereotypes that have historically surrounded the black male body. Yet, rather than fetishizing or objectifying his subjects, Mapplethorpe’s lens treats them with a sense of reverence and idealization, drawing comparisons to classical representations of the human form in Renaissance sculpture.

Similarly, his exploration of queer sexuality and BDSM culture is not merely sensationalist but deeply rooted in a desire to depict the full spectrum of human desire. For Mapplethorpe, these subjects were not just about shock value but about confronting the viewer with the complexity and multiplicity of sexual identity. His photographs ask us to reconsider the boundaries between the beautiful and the grotesque, the sacred and the profane, the public and the private.

Mapplethorpe’s still lifes, particularly his images of flowers, also reflect this preoccupation with beauty and death. In these photographs, flowers are not simply objects of beauty but symbols of fragility, decay, and the passage of time. The perfect symmetry and lighting in these images elevate the flowers to the status of sculptures, yet there is always a sense of impermanence and transience, reminding the viewer of the fleeting nature of life and beauty.

This tension between beauty and death, pleasure and pain, is perhaps most evident in Mapplethorpe’s self-portraits. In these images, particularly his final self-portraits taken after his diagnosis with AIDS, Mapplethorpe confronts his own mortality head-on. These images are stark and unflinching, yet there is a sense of control and composure in the way Mapplethorpe presents himself. Even in the face of death, he remains the master of his own image, using the camera to capture not just his physical form but his enduring presence as an artist.

The Controversy and Legacy

Throughout his career, Robert Mapplethorpe courted controversy. His explicit depictions of gay sexuality and BDSM practices, particularly in his X Portfolio, sparked debates about the role of art in society and the limits of free expression. In 1989, just months after his death, the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., famously canceled a planned retrospective of Mapplethorpe’s work due to concerns over its explicit content. The exhibition, titled The Perfect Moment, became a flashpoint in the culture wars of the late 1980s, leading to widespread debates about censorship, public funding for the arts, and the representation of marginalized communities.

Yet, despite (or perhaps because of) this controversy, Mapplethorpe’s legacy has only grown in the years since his death. His work is now celebrated for its technical mastery, its bold exploration of identity and desire, and its contribution to the ongoing dialogue about the role of art in society. Major retrospectives of his work have been held at institutions such as the Guggenheim Museum, the J. Paul Getty Museum, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, cementing his place in the canon of contemporary art.

More than three decades after his death, Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs continue to provoke, challenge, and inspire. His ability to fuse classical notions of beauty with modern themes of identity, sexuality, and power remains unparalleled, and his work continues to resonate with audiences today. In an era where questions of identity, representation, and free expression are more relevant than ever, Mapplethorpe’s art serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of pushing boundaries and challenging the status quo.

The Eternal Provocateur

Robert Mapplethorpe’s art is a study in contradictions. It is at once beautiful and unsettling, classical and modern, reverent and transgressive. His ability to capture the complexities of human identity—its beauty, its fragility, its desires—sets him apart as one of the most important and influential photographers of the 20th century.

Mapplethorpe’s legacy is not just in the images he created but in the conversations he sparked about art, identity, and power. His work challenges us to look beyond the surface, to confront our own preconceptions, and to see the world in new and unexpected ways. And in this sense, Robert Mapplethorpe remains not just an artist but an eternal provocateur—a voice that continues to push the boundaries of what art can be.